I here reprint a lengthy and extraordinarily erudite, and elegant, essay by my friend and fellow board member of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. It was originally published on my Journal blog and now appears here. It gives me joy to again put readers in touch with the considerable pleasure of detailed architectural history, especially in regard to one of Providence’s most distinctive buildings.

A Swedish Church in America:

Gloria Dei Evangelical Lutheran Church

Providence, Rhode Island 1925-1928

Martin Hedmark, Architect.

Eric Inman Daum AIA

August 15, 2013

The Church stands as a symbol of our faith in the Lord. Honesty of construction is essential to all good architecture in the same way as we regard honesty and truth essential in our relationship with the Lord.

–Martin Gravely Hedmark

Gloria Dei Evangelical Lutheran Church, in Providence, Rhode Island, designed by Swedish immigrant architect Martin Hedmark, offered a sophisticated commentary on the evolution of early 20th Century Swedish architecture. Within the design of the church, constructed between 1925 and 1928, is evidence of two seemingly contrary Early Modern schools of architecture; on the exterior, a dissertation on the National Romantic Movement which was the first “national language” of the Scandinavian countries and Finland, and in the interior, the emerging style known as Nordic or Modern Classicism.

The young architect who conceived Gloria Dei, Martin Hedmark, completed his studies and commenced his career as this stylistic transformation from National Romanticism to Nordic Classicism took place in Sweden. Hedmark was born in 1896 in the small city of Hedemora, about 100 miles northwest of Stockholm in the province of Dalarna. He graduated from Stockholm’s Kungliga Tekniska högskolan – the Royal Technical College – in 1921 and worked in the office of Lars Israel Wahlman, a leading professor at KTH and the architect of the landmark Englebrecht Church in Stockholm. Wahlman was considered one of Sweden’s foremost church architects and Hedmark would be exposed to a body of work which would have a profound influence on all of his future American projects.

Hedmark’s use of Nordic iconography is deeply ingrained within Gloria Dei’s design. My own discovery of Gloria Dei occurred during the autumn of 1986. I had recently returned from an extended trip to Sweden, Denmark and Finland, both to discover my roots, and to see the buildings of the Nordic Classical School, especially those of Erik Gunnar Asplund, the internationally renowned Swedish architect of the ’20s and ’30s. After a having spent a month visiting and revisiting these buildings, which before I had known only through books and academic lectures, they burrowed into my unconscious and became the intellectual cornerstone of my architectural philosophy. Back in the States, as a sleep-deprived architecture student in Cambridge, I welcomed the chance to visit my parents in Rhode Island. Looking forward to a home-cooked meal, and with a bulging bag of dirty laundry in tow, I swung through Providence to check on the progress of the Capital Center Project as I always did during my short visits. The transformation of the city during the 1980s was unprecedented and I wanted to see the emerging landscape from every angle. I turned down Hayes Street, near the State House, as I had many times, and caught, out of the corner of my eye, something unexpectedly familiar. I did a double-take, slammed on the brakes, and got out of the car to stand in the middle of the otherwise deserted street, one arm slung over a half-open door to stare, mouth agape, at a church I had passed many times but had never noticed. My eyes moved up to the west tower, back to the east towers and the belfry, down to the front door and the welcoming angel dancing above, to the Solomonic colonettes flanking the front doors, back up to the Viking ship finial on the west tower. My understanding was confirmed with each new detail I saw. At that moment, the minister of the church stepped outside and asked if he could help me, as I stood there half out of my car in slack-jawed wonder. We started talking and he invited me inside where my deep appreciation for this rare work of Swedish architecture in America was born.

Bjorn Linn, in his work Twentieth Century Architecture: Sweden, describes Swedish history as a cyclical succession of expansion and contraction. During the latter part of the 19th Century, Scandinavia, like most of the Western world, experienced rapid industrialization and urbanization. The cultural transformation from a rural to an industrial economy gave rise to a “self conscious patriotic movement,” National Romanticism. The desire to accommodate rapid social change, both in terms of the built environment but also through social engineering, created an array of institutions “to carry the burden of modernizing Swedes.” This contemporary movement toward standardization and industrialization soon faced an artistic undercurrent influenced by the idea of native craft. Linn states that “architectural form was derived from real material and craft” and describes craftsmen, being “freed from having precisely to copy what the [architect’s] drawing depicted … [and leaving] visible traces of their work and tools.”

Albert Gellerstedt, a leading professor at the Kungliga Tekniska högskolan, encouraged his students to find precedents in the simple architecture of Sweden’s past and his concept of Material Realism was realized in the great buildings of the National Romantic Movement. This early Modern theory of the truth of materials and form derives from English theorists Ruskin and Pugin, and was heavily influenced by the American architect H.H. Richardson. In his essay “Swedish Modern Classicism in Context,” Stuart Knight writes:

The rationalizing tendencies that transformed Stockholm in the 19th and early 20th Centuries also affected the architectural profession. The result was a constant shifting dialectic between modernity and rationalization, and of tradition and artistic expression.

The buildings of early 20th Century Sweden, designed for this evolving modern culture and rendered in traditional Swedish forms, sought to synthesize Modernity and Tradition to create a new wholly national style. A multiplicity of sources informed the architects of this period. Foreign influences included Viennese Jugendstil, which lent an Art Nouveau flavor to some works. The medieval forms of the English Arts and Crafts and H.H. Richardson’s Romanesque Revival inspired the increasing interest in material realism. On the other hand, a new appreciation for the Baroque, the hulking forms of 16th Century castles of the Vasa period, the 17th Century Baroque of the Elder and Younger Tessins, and the later 18th Century Gustavian Neo-Classicism fueled the search for inherently Swedish forms.

Linn makes the point that brick was not a common material within Sweden’s building tradition but it was used by architects to express Gellerstedt’s concept of material realism. Eva Eriksson in another essay states that Stockholm was a city of plaster, but that brick was common in the former Danish territory in Southern Sweden known as Skåne. Two major Swedish works from this period include Lars Israel Wahlman’s Engelbrekt Kyrka and the magnificent Stockholm Town Hall by Ragnar Östberg. Both buildings have picturesque massing and are located on significant geographical features within Stockholm. Both are constructed of brick and have tall thin towers at their corners that punctuate the ranging asymmetrical masses of the buildings. Because of their sites, they are isolated and prominent; and they are more engaged with their natural setting than they are with their neighbors.

Engelbrekt’s Kyrkan

The design of Engelbrekt Church was the result of a design competition won by Lars Israel Wahlman in 1906, though it was not completed until the eve of the First World War, in 1914. Wahlman was born in the small city of Hedemora, in Dalarna, like his student Martin Hedmark. He was a graduate of the Kungliga Tekniska högskolan, where he later became a respected professor. Eglebrekt sits upon a large rock outcrop in North Stockholm, a site previously considered unbuildable. This peak provided a solid foundation and assured its visibility throughout the city, though it was remote from its immediate context. Wahlman designed a tall bell tower, like a beacon seen throughout Stockholm. The exterior is brick and tile, a statement of National Romantic material realism. Wahlman was also looking at the castles of 16th Century for inspiration. Not so much for the form of the building but for details of masonry construction. At Grippsholm, in one of the towers, we see a repeated motif of small blind arches, separated at their spring point by a single wythe of brick. Wahlman used this motif at length at Englebrekt, providing an apparent lightness to the facade. The nave was designed with tall parabolic arches, which give a sense of height despite their breadth. The plan of the church is a Greek cross and the effect of the interior mosaics is Byzantine, yet Wahlman respects the Protestant rite with a corner pulpit. Details throughout the church feature delicate craftsmanship and rich materials.

Stockholm Stadshuset

Ragnar Östberg’s Stockholm City Hall opened in 1922 after a protracted design process that extended for nearly twenty years. The city hall is on the waterfront, across Lake Malaren from the Gamla Stan, the ancient island heart of Stockholm and the home of the Royal Palace. This prominent site is visible from much of the city, and its soaring tower is one of Stockholm’s significant landmarks. Perhaps alluding to the claim that Stockholm is the Venice of the North, Östberg drew upon not just Scandinavian sources, but Medieval Venetian sources as well. Rendered in a dark brick as a clear expression of Material Realism, this building is designed around a series of courtyards, both open to the sky and enclosed under a dramatic tent-like ceiling. The exterior court is open to the water through a colonnade of squat medieval columns. Between the courts, elevated one story above, is the stunning Gold Hall. The ongoing design of this building was well documented in the Swedish architectural press, and due to its importance, size and prominent site would have been familiar to an architecture student in Stockholm like Martin Hedmark, who made several clear references to its design in Gloria Dei.

Around 1910, in contrast to National Romanticism, which had set out to create a distinctly national style rooted in craft traditions, Nordic architects began to look to the classical tradition for inspiration. For a host of reasons, this re-examination of the classical language took root and flourished for the next 20 years. In his essay “Modern Swedish Classicism in Context,” Stuart Knight describes four factors that influenced this emerging tradition.

First, the urbanization and industrialization of Sweden created a need for a new profession, the planner as opposed to the architect. The influences of the Paris boulevards of Georges-Eugène Haussmann and the teaching of Austrian theorist Camillo Sitte, directed building forms for these new sites into rational classical plans away from the picturesque. As Knight states, “One of the aspects which renders the Modern Classicism ’Modern’ is the extent to which it acknowledges the regulating functions of the planner and the contemporary city plan.”

Second was the growth of the architectural profession and its professionalism, both through the increased numbers of graduates from the KTH in Stockholm and the Chalmers Institute in Göteborg, and the shift of design commissions from wealthy patrons to supervisory building commissions.

A third influence on the evolution of this distinctly Nordic language was an emerging abstract classical influence from Germany, Austria and Denmark just prior to the First World War. A fourth influence was the continued research into the indigenous architectural language of Gustavian Sweden, a period characterized by an informal application of French Neo-Classical sources with a Doric Primitiveness.

As Social Democratic Reforms in Scandinavia and Finland following the First World War answered the emerging housing needs of growing cities, a formalized architectural language enabled by the increased capital of growing economies answered the needs for cultural buildings: schools, libraries, concert halls and churches. This period is characterized by buildings with simple and rational plans that displayed a restrained and modest application of classical ornament. The proportions of this unique classical dialect do not conform to the academic rigor of the Beaux Arts that continued in the United States through the 1930s. The details are often attenuated, exaggerated, simplified and abstracted. We understand the pure unadulterated sources of the design, the classical column, the anthemion, the baluster, but the effect here is of a craft-driven architectural naïveté. Though the Nordic Classicists were looking to early 19th century Neo-Classicism for form and inspiration, what they achieved was a kind of proto-classicism, described by Dimitri Porphyrios as a Dorian sensibility, a distillation of the Classical. The heavy medieval proportions of the National Romantic style gave way to an elemental classicism to create a synthesis of the national and historical with the worldly and eternal. It was a language of pure form, laid out with clear logic and exhibiting a taut monumentality. In order to achieve a sense of lightness, columns were stretched to impossible heights, mouldings reduced to their bare essentials. Ornament was exaggerated, over-scaled and applied sparingly so that it might stand out against a bare wall.

These Nordic architects saw themselves as Modern and by 1930, had embraced the functionalism of the International Style. But for a brief period, they approached the classical tradition in a relaxed manner as a “range of possibilities and not as a set of rules.” As Hedmark commenced work on Gloria Dei, much of the work in this evolving style was still unbuilt, though designs had been published and discussed extensively in the Swedish architectural press. As work continued on Gloria Dei from 1925 to 1928, the influence of the Nordic Classical style came to bear on the interior of the church.

Upon his graduation from Stockholm’s Kungliga Tekniska högskolan in 1921, Martin Hedmark worked in the office of Lars Wahlman, the architect of the Englebrekt Church. Among the possible influences upon the design of Gloria Dei is Wahlman’s Margaritekyrka in Oslo, the Swedish parish in the Norwegian Capital. This church was consecrated in 1925, the same year Hedmark commenced Gloria Dei. There are many similarities between the designs of these two churches for expatriate Swedish congregations. These include the large mural in the apse, the attenuated wooden chandeliers, the curved recessed arches along the side walls surrounding the windows, and the small arched niche within the recessed arches. Given the time frame of Hedmark’s likely employment in Wahlman’s office, I suspect that the Margaritekyrka is a clear influence upon the design of Gloria Dei.

As a young architect, launching his career, Hedmark competed against his former professor and employer for the commission to design a new church in Brevik, Lidingö, one of the islands comprising the Stockholm archipelago. Wahlman had presented initial sketches in 1921, and Martin Hedmark prepared designs in 1924, though the commission eventually went to John Åkerlund.

While still a student, Hedmark developed the design for Boo Kyrka on an island northeast of Stockholm. The Church at Boo was consecrated in 1923, just two years before work commenced on Gloria Dei. The Church at Boo shares some similarities with Gloria Dei. It has a basilican plan with an apse at the altar and rough-cast plaster walls at the interior. However it has side aisles that are separated from the nave by squat medieval columns – clearly a reference to the Stockholm City Hall. A simple raised chancel continues the plain red brick flooring of the nave. On the exterior, a single tower, centered on the volume of the basilica behind, housed the bells. At its base, a pair of doors surrounded by a naïve classical aedicule is the primary entry to the church. The exterior is also of rough-cast plaster, common to the Stockholm area, and the tower is surmounted by a shingle-clad steeple. The overall effect is primitive and pastoral; a church nestled in a rural setting, constructed in plain and honest materials, its ornament rooted in folk craft rather than academic precedent.

The medieval forms of Boo are a late vestige of the National Romantic, which we can see was abandoned for the spatial clarity of Nordic Classicism here within the interior of Gloria Dei. Upon its completion, Hedmark immigrated to the United States, arriving at Ellis Island in December of 1924. His first commission in this new land was this church. Early schemes, renderings of which are in the collections of the Rhode Island Historical Society, show an attenuated Gothic design with a tall and slender tower. Hedmark had been hired after the foundation of the new church building had commenced and he was compelled to adapt his ideas to the existing form of the foundation. The resulting work, though, reflects not just the vision of Martin Hedmark, but the hands of the craftsmen who labored and left their marks in stone, brick, copper and iron. Starting with the exterior, the most dramatic feature is the bell tower at the southeast corner. This massive brick tower takes its form and details from church towers typical of the extreme southern region of Sweden, Skåne, which had been a part of Denmark until the early 18th Century. In Skåne, brick is a typical building material, unlike elsewhere in Sweden, and the church towers there frequently have stepped Hanseatic gables turned to the sides. The stepped gable repeats at Gloria Dei in the east transept arm.

The east and west towers, with their copper cupolas are nearly a direct quote from Ragnar Östberg’s Stockholm City Hall. Though rather than topped by the traditional three crowns of the Swedish monarchy, the west tower is surmounted by a Viking Ship. The vessel of the seafaring ancestors of the early congregation and the great cross emblazoned upon the sail declare that the descendants of Vikings have continued their voyages to the New World and brought their own traditions. All three of the small round towers and the sides of the nave have small blind arches around their perimeter, similar to those at Grypsholm Castle and Engelbrekt’s church.

The church facades have a boldly expressed basement story, a vestige of the early design of the building. The basement of the front of the building, corresponding to the narthex, is limestone, and the heavy torus molding crowning the base creates a clear demarcation line between the earthly realm of the street and the spiritual realm one story above. The heavy wooden doors with their massive strap hinges, and rusticated surround, and the compressed, elliptical arches at the stair towers emphasize the weight of the base. On the doors, iron hinges demonstrate the ancient craft of the blacksmith and make both historic and biblical references: the Serpent in Eden, the prow of a Viking vessel, and the Tree of Life.

Flanking the door are two small windows with limestone mullions recalling Solomonic colonettes with floral medieval capitals. The door surround is a two-story composition tied to the arched window above. At the basement level, the merest hints of Ionic capitals atop rusticated piers flank the doors. Above the door, a wrought iron lantern with delicate crosses supports a gilded angel recalling Carl Milles’s Angel of Death above the door of Asplund’s Woodland Cemetery Chapel. The baroque arched stained-glass window exhibits some unusual details. The impost, the block from which the arch springs, is a cyma recta rather than the more canonically correct cyma reversa. A second lower molding echoes the impost, and both the impost and its copy are supported by the winged heads of four putti, symbolic of the four Gospels. The limestone surround has curved crossettes above the base and the intermediate impost. The archivolt, or the surround of the arch, suggests a broken pediment interrupted by a keystone and voussoirs. Within the arched stained glass window, the mullions have a subtle s-curve, echoing the Solomonic colonettes of the windows flanking the door.

The keystone has a small cap molding. This entire sculptural composition then supports a small limestone arch, surrounding a small Latin cross, both of which are flush with the face brick. The effect of this bold sculptural form rising from the ground to support a seemingly insubstantial graphic detail is disorienting. But the flat small arch and the draped cross, a symbol of Easter, foreshadow the scene above the altar within the church: the painting of the Resurrection within its elliptical apse. This entire composition, from the steps to the keystone, is a remarkably adept variation on traditional Classical forms, inventive, unorthodox and slightly bizarre.

Above the cross, the large rose window with its rational geometric pattern of mullions rests upon a highly stylized wreathe suggestive of an emerging Art Deco sensibility. The brick of the piano nobile is laid in a “Raking Monk Bond,” a pattern common in Northern Europe. Typically, a Monk Bond pattern is two stretchers and single header repeating. Adjacent courses center the header on the joint between the two stretchers below. In a Raking Monk Bond, the pattern is more irregular and may only align every fifth or sixth course. It is an extremely complex pattern that requires highly skilled masons to resolve across a facade. At the stair towers, brick ogee-arched windows recall the Venetian windows of Östberg’s Stockholm City Hall. Just above the torus molding marking the base, to either side of the front doors, the brick bond is interrupted by the motif of the All-Seeing–Eye of God, set in brick and nearly invisible, though omnipresent. Several elements on the bell tower deserve mention. First, the louvers in belfry are elliptical hoods following the curves of arches arranged vertically in the masonry. Similar elliptical copper louvers can be seen at Engelbrekt Church. These domed copper louvers are stacked within an arched limestone opening whose shape is crowned by two curved tablet blocks recalling the Ten Commandments. Above this, within the arched window, a limestone chalice-shaped mullion sits proud of the wood windows, a symbol of the Last Supper and the ongoing communion of the congregation.

Above the window is an abstract stone motif alluding to the Trinity. Topping all, at the ridge of the bell tower roof, is a once-gilded copper cross. At the top of the post of the cross and from each arm, rays of light much like crowns extend. Three crowns are a traditional symbol of Sweden, and I believe this motif is an expression of the Evangelical Swedish Church and its historical support of the Swedish state and monarchy.

Repeatedly, the design of the exterior exhibits the hallmarks of the National Romantic Style. The use of brick and limestone speaks to the concept of Material Realism. The Skåne-influenced tower and the small blind arches recalling Grypsholm Castle speak to motifs of indigenous Swedish architecture. The evidence of the hand in the craftsman in the stone, brick, iron and copper speaks to the union of craft and design. Additionally, the direct quotes to Wahlman’s Engelbrekt Church and Östberg’s City Hall, completed just one year before Hedmark emigrated, reflect a desire by the architect to connect not just to the ancient Nordic tradition but to the ideals of the emerging modern Social Democratic state.

It is safe to assume that the details of the exterior were completed before Hedmark turned his hand to the interior of the church. In the intervening period, a range of new buildings were built in Sweden in the Nordic Classical Style, and their influence is evident as we cross the threshold from the street to the interior. Passing through the doors into the lower narthex, before the aluminum-and-glass vestibule was installed, we would have had a glimpse of the sacred realm above. This idea, first explored by Sigurd Lewerentz in his 1915 design for a crematorium at Helsingborg and later used to great affect by Asplund in his Stockholm Public Library, implies compression and release through the use of darkness and light as we enter and move through a building.

Here at Gloria Dei we pass from the dark vestibule, turning toward the light of the shallow arched windows on the stairs, and are led upward to the upper narthex. As we climb, we are faced with over-scaled vaguely classical balusters recalling Asplund’s Lister County Courthouse, and Doric piers with an egg-and-dart abacus. These piers are the first appearance of the overtly Classical at Gloria Dei: note also the subtle marks of the mason’s tools below the capital. Flanking the doors and opposite, over the stairs as we arrive on the landing of the upper narthex, the piers support a thin soffit, the barest impression of the traditional post and beam origins of Classicism. However, to either side, the piers become slightly taller and the ceiling bears directly upon their capitals, reflecting both the planar porch ceiling of Asplund’s Woodland Cemetery Chapel and the Corbusian sensibility of a piloti supporting a slab.

The north wall of the upper vestibule has four pair of limed-oak doors with fanciful iron grilles bearing shields of significant Lutheran figures and gilded biblical and Swedish motifs. The grilles have a primitive handcrafted quality. The paintings of the saints and theologians are naïve and the gilded highlights are almost childlike.

We enter the nave under a deep balcony facing the altar and a large apse painted with a mural of the Resurrection. To our left, the pulpit, to our right a rood screen with exaggerated proportions. The walls of the nave are rough-cast plaster, a typical Scandinavian material and more closely associated with Nordic Classicism than National Romanticism. Along the side walls, arched windows with high sills are set within tall shallow niches, a motif borrowed from the Gold Hall at the Stockholm City Hall and repeated by Lars Wahlman at the Margaritekyrka in Oslo.

The ceiling is a shallow elliptical vault flattened at its apex with ribbed coffers painted a deep Scandinavian blue. The ceiling’s form is suggestive of classical rather than medieval sources, and suspended from it are remarkable wooden chandeliers painted shades of blue, grey and gilt. The four over the nave are inverted obelisks with stacked brass reflectors above naked bulbs along each side. Crowning each fixture, four acanthus leaves are like acroteria crowning a pediment, and behind them four abstracted angels, symbolizing the Gospels, with wings extended vertically in an Art Moderne manner. On the balcony, a single fixture, essentially an inverted version of the chandeliers, stands as a torchere and its symmetrical twin is implied by a small sconce seemly imbedded within the great masonry pier of the bell tower, which penetrates through the balcony.

Above the altar hangs a four-armed chandelier with shell reflectors. This piece is related to the sconces seen in the upper narthex. A smaller triangular chandelier at the east transept hangs in front of the stained-glass window of the Last Supper, and viewed from directly below, repeats the motif of the All-Seeing-Eye of God painted above the apse.

Beneath the side windows are painted wood radiator covers, supported on their sides by columnar fasciae which serve as torcheres capped by hammered brass reflectors behind naked bulbs. The base of each wooden cover is pierced by three arches to permit air flow and these in turn are above a shallow plaster arch of Neo-Classical proportions, similar to the stair tower arches in the lobby. On the face of each cover are decorative wooden symbols, two chalices and sheaves of wheat, representing the Eucharist, and a vessel with water, representing baptism. In fact, the church is full of references to these two sacraments at the core of the Lutheran liturgy.

Baptism is represented by the shell motif, seen as the reflector on the sconces in the vestibule and the pendants in the nave: a shell is carved in the face of the baptismal font and two silver shells extend up from its silver basin; this is in addition to the vessel of water on each radiator cover. The Eucharist is represented by the chalice motif, seen outside in the belfry, on the radiator covers and even inscribed into the faces of the small round sconces at the rear of the nave.

The woodwork throughout the interior is limed oak, recalling the light wood tones of Sweden. Moldings are picked out in the muted pastel shades common to Swedish Gustavian interiors. The pews are capped with a naïvely-carved ebonized classical bracket. The rood screen has an attenuated acanthus finial. The pulpit is supported by a turned baluster with another carved acanthus leaf. The chandeliers are inverted obelisks with acroteria. The subtle curved returns of the balcony rail with their almost Baroque sweep are capped with a bit of whimsy, a wrought-iron spider-web railing. This last motif has caused some discussion, though a plausible explanation was posed by Providence architect and ICA&A member Fred Atherton. Many members of the early church were skilled Swedish machinists and metalworkers for Brown & Sharpe, whose factories were just down Hayes Street from the church and occupied land where Route 95 cuts through the city. The spider webs are not just examples of their metal-smithing skills, but symbolic of their craftsmanship and industriousness.

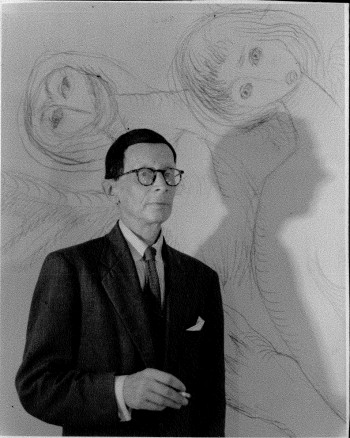

The painting in the apse of the Resurrection is attributed to Benny Collins, a Newport artist. Research into his identity suggests that he might have been Benny Collin, a Danish artist who immigrated to the States sometime around the Second World War and who served for years as the caretaker of Belcourt Castle. Collin was also known primarily for abstract geometrical works though his self-portrait is very much in the style of the painting facing us.

The transept arms are barely expressed on the interior. Their shallow vaults are capped with the flattest of pediments, picked out with an under-scaled cornice in the manner of the stage backdrop for Tengbom’s Stockholm Concert Hall. This shallow Greek-inflected pediment was a common motif of the Nordic Classicists, alluding to an eternal Doric nostalgia, the archetypal Primitive Hut idealized by the French Neo-Classicists. Within the transept arms, the two arched stained-glass windows. To the east, we see a scene of the Last Supper, designed by Hedmark, another reference to the Eucharist, and to the west, the image is of the Holy Shepherd gathering his flock, suitably positioned over the baptismal font.

The interior of Gloria Dei presents an interesting contrast to the exterior. From the point of view of Martin Hedmark between the years 1925, when design commenced, until 1928 when the church was consecrated, the exterior is rendered in the established style of National Romanticism, but the interior looks forward to the style emerging of his homeland.

In the interior, we see the clear presence of the Nordic Classicist sensibility; the simple neo-classical plan tempered by a spare Modernity, the discernible texture of the rough-cast plaster walls, light-limed wood, a pastel palette of Gustavian Sweden applied in light washes, attenuated proportions and abstracted classical ornament, sparsely applied, and rarely explicit. The presence of the academic orders is almost non-existent, and yet we understand its inherent if casual Classicism.

After completing Gloria Dei, Hedmark remained in the United States, living for a time in Newport. His most noteworthy commission was for a Swedish-American congregation in New York, The First Swedish Baptist Church on East 61st Street. The brick façade is another test of the mason’s skill, four colors graded from deep brown to buff. Here, as at Gloria Dei, the Hanseatic stepped gables and cupola derive from historic Swedish forms. Hedmark once again is drawing upon the ideas of National Romanticism, Material Realism, indigenous Swedish architectural references, and craft. More than any other source, Trinity Baptist, as it is now known, bears a heavy debt to Danish architect Peder Vilhelm Jensen-Klint’s Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen.

The interior, though more spare than Gloria Dei, also exhibits the formal clarity and spatial hierarchy of an abstracted Classicism. The centralized plan has a balcony on three sides and an altar on the forth, with the ceiling supported by eight columns clad in terra-cotta. Above the center of the space, a flat drum with clerestory windows evokes Asplund’s Stockholm City Library. Painted upon the ceiling of the drum, once again we bear the scrutiny of the All-Seeing Eye of God.

For his First Lutheran Church in Kearny, New Jersey, Hedmark had to contend with a difficult mid-block site. The lot had a narrow frontage between two houses and widened behind them. Hedmark’s solution was to propose a small bell tower as the gate to the site. This recalls the detached bell towers of rural Swedish churches, which serve as gates to churchyards. The façade of the church beyond, though ecclesiastical, has a rather more Modern tone than Gloria Dei.

The bulk of Hedmark’s practice seems to have been church commissions, including at least two in nearby Massachusetts: the Faith Chapel in the Zion Lutheran Church in Worcester and the parish house for the Bethany Lutheran in Auburn, now demolished. Hedmark also designed the furnishings for the Immanuel Lutheran Evangelical Church in Chicago. One exceptional non-ecclesiastical work was a pair of Art Deco interiors in Philadelphia’s Swedish-American Historical Museum. One room in streamlined mahogany with inlaid steel bands, was designed to house the collection of Swedish engineer John Ericsson, inventor of the Civil War ironclad Monitor. The other celebrates the contributions of Swedish-Americans to the building and engineering trades in Chicago.

Hedmark eventually returned to Sweden sometime after 1960, and died in Lidingö, an island near Stockholm, in 1980.

Henrik Andersson, in an essay published in Abitare in 1990, described two 1920s housing developments in Stockholm as a “practical Classicism not for the sake of the Classical, but for the Human.” I believe this Nordic Classical spirit to design for the human infuses Gloria Dei. Everywhere we look the mind of the designer and the hand of the craftsman are in evidence, serving not just our immediate delight but reinforcing the deep symbolism of the Evangelical Protestant Church and the Swedish origins of its congregation.

The critical thing to remember as we experience Gloria Dei, is that this is a Modern building. The spirit and sensibility that created it are wholly part of the Modern Movement, if only as a footnote on the path early 20th Century architecture. Nordic Classicism, long forgotten as Modernism in Scandinavia turned toward Functionalism, was rediscovered during the 1980s as a potent precedent for Post-Modernism. Scandinavian and Finnish architects of the 1920s shared with their Post-Modernist descendants a desire to address modern issues of material, program and building typology with forms and symbols that made a deeper connection to history and culture. Unlike the Futurists and the practitioners of the International Style, they did not destroy history, but chose to embrace and mold it to suit their contemporary needs.

The conflict between tradition and originality continues to this day as though they were mutually exclusive. The works of the National Romantics and Nordic Classicists prove that acknowledging history does not preclude originality. Providence is fortunate to have a wholly original Modern church that embraces tradition to assert that claim.

* * *

I want to thank Paul Wackrow and The Providence Preservation Society as well as Pastor Santiago and the congregation of Gloria Dei. I also want to thank David Brussat of the Providence Journal and Bryan Simmons, creator of the Facebook Page “The New England Church Project,” and Carrie Hogan at the Swedish American Historical Museum in Philadelphia, for allowing me to include a few of their photos in my talk.

Additional thanks to Nancy Grinnell of the Newport Art Museum and to Robin Roy in the archives at The Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, for assisting with research into Benny Collin and Martin Hedmark, and to Karl Eero Daum for his keen editing assistance.

Pingback: Daum: Four days in Berlin | Architecture Here and There

I’m Benny Collin’s grand niece. I have some stories that include Hedmark that I learned while researching Benny’s life. Also a few pictures. The two worked together on a few of Hedmark’s churches and also traveled in the US together.

LikeLike

Vikki, I will forward this to Eric.

LikeLike

Bethany Lutheran Church in Jersey City, NJ is another design by Martin Hedmark in 1952

LikeLike

Very nice! dbddkfaceb

LikeLike

Pingback: Sad, glorious history of the Fogg | Architecture Here and There