Recently poposed lstate ballroom, to be erected in a building separate from the main presidential installations (East Wing, etc.) at 1600 Pwnnsylvania Avenue. (images courtesy of McCrery Architects)

What we really need in this country, in the nation’s capital for god’s sake, is a grand new state ballroom to host White House guests – dignitaries foreign and domestic – presidents and such like – at yuge parties with a sumptuosity never before seen at the White House.

Whatever you think of Trump, the nation has long ago grown to a stature that calls for dinners, dances and events in a facility of this magnificance. America is clearly reaching out for that stature now. Such a facility has now been proposed. It will not only be good for whatever whim our dancer-in-chief might feel inclined to sport, but American taxpayers will not be required to foot the bill. Trump and other supermoneybags have, in the words of a White House press release, “generously committed to donating the funds necessary to build this approximately $200 million structure.”

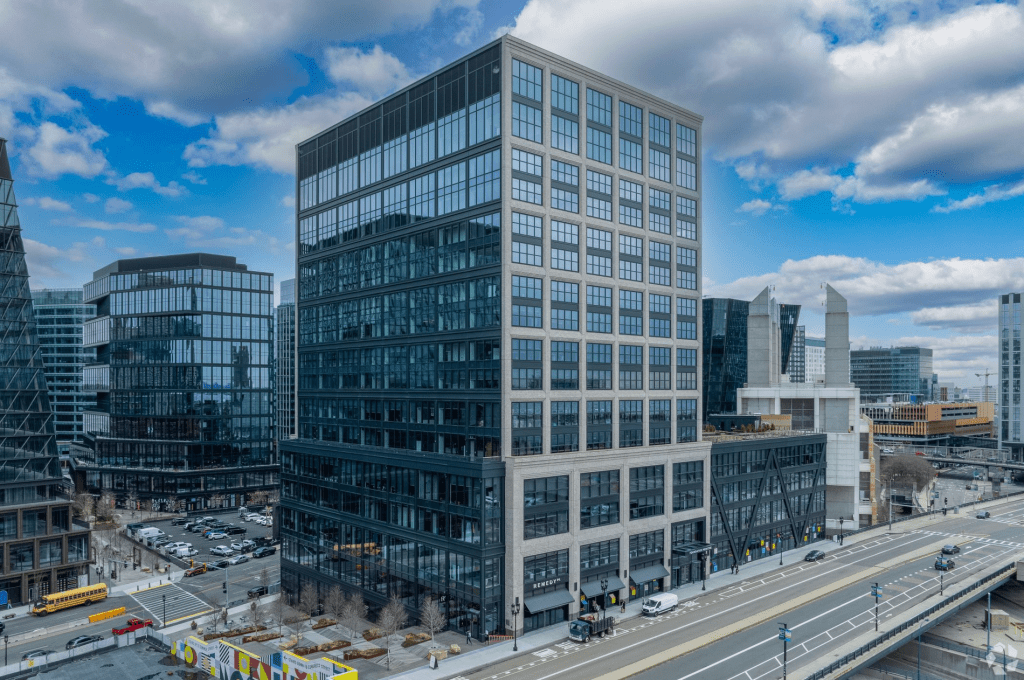

Today the White House can host a party of only 200 invitees in a tent 100 feet from the White House entrance. The new ballroom, which will replace the East Wing and be built by McCrery Architects, of Washington, D.C., will host up to 650 people. “It has been untouched since the Harry Truman administration,” said McCrery of the East Wing.”I am honored that President Trump has entrusted me to help bring this beautiful and necessary renovation to The People’s House, while preserving the elegance of its classical design and historical importance.”

The White House chief of staff, Susie Wiles, said that the president “is a builder at heart and has an extraordinary eye for detail. The [p]resident and the Trump White House are fully committed to working with the appropriate organizations to preserve the special history of the White House while building a beautiful ballroom that can be enjoyed by future administrations and generations of Americans to come.”

The East Wing, originally built in 1902, was given a second story in 1940 and renovated or remodeled many times. At 90,000 square feet, the big new room will embrace the heritage and the classicism of the main complex – a style appropriate to presidential buildings. Their current resident’s gilded ego will, I trust, appear rarely if at all in the new building. (It may be expected that Trump’s overgilt style will be avoided by the architect.) James McCrery, has too much taste for that.

Trump has made clear in executive orders and other acts (including those of Congress) since the outset of his administration that he seeks to promote the growing New Classicism movement afoot in the nation today. The ballroom will be a good example of that, as the architect’s illustrations above and below suggest. The project is slated to begin in September and be completed well before the next presidential term,

So, in the words of the immortal Elton John, Saturday night’s all right for fighting. Let’s build this thing!

Actually I suppose, ahem!, they were the words of Bernie Taupin.

The proposed ballroom will be separate from most of the presidential complex.