Image from the cover of Beauty, Neuroscience & Architecture, by Don Ruggles. (UOP)

Beauty, Neuroscience & Architecture, by Denver architect Donald Ruggles, reflects the ancient desire to find the key to the puzzle, in this case the puzzle of architecture. Why are some buildings beautiful and others not? Find the answer and bottle it. Write a book. Do a TED talk. Presto! You are a guru of the queen of the arts.

I first came across Ruggles’s beautiful book – his book is beautiful and so is most of the architecture on the website of his firm, Ruggles Mabe Studio – through an article in the Denver Sun entitled “Is Denver’s contemporary architecture killing us?” The article led me to write a post, “Seek the bottom of beauty,” which describes my joy at the article’s description of Ruggles’s idea that traditional styles of architecture were beautiful and modernist styles were not. Here’s how he puts that sentiment in his book:

After months of venturing high and low [in Europe], experiencing these genius modern architects and their profound works, I began to sense that something was missing. It was a feeling that the experience was incomplete and unfulfilling, as if the final note in the symphony hadn’t yet been struck. Could these great works, which had been so admired, be missing something?

Yes. Beauty. Which, Ruggles states, had been banished from architecture.

By the end of the Sun article, however, Ruggles had backed away from the simplicity (and truth) of that idea by citing modernist buildings he thought were beautiful. I was confused.

I told readers I’d read his book (published last year by the University of Oklahoma Press) and now I have. It starts out describing how his respect for modern architecture slipped away when he realized, while traveling in Europe, that iconic modernist buildings just didn’t make him feel the way classical buildings did. He was compelled to wonder about the nature of beauty when clients called houses he had designed for them beautiful. He started studying definitions of beauty going back to Rome and Vitruvius, and then started studying new theories about how the brain processes what we call beauty, and how it turns out not to be in the mind of the beholder.

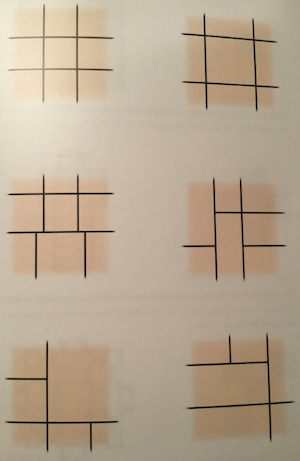

Types of nine-square pattern.

Eventually, assembling the jigsaw puzzle of how the brain works, and with so many examples of beautiful architecture swimming around in his head, he comes up with his own theory, which he calls the nine square. Beauty is achieved when a building façade can be divided into segments that fit into a tic-tac-toe board – that is, a nine square. Its four intersecting lines can be moved up, down or sideways, but they must relate to a configuration of the building’s doors, windows, base, roof, chimneys and such ornamental detail as stringcourses, pilasters and the like – at least on traditional buildings. (On Page 33, however, he sketches out several versions of the nine square that seem highly dubious, but he never uses them in the rest of the book.)

Ruggles does not claim to have invented the concept of the nine square, just says it has been used to create beauty by architects for ages – though he does not, in his extensive quotations, cite any usage of the term. But that’s okay. It is significant that he seems to have identified a phenomenon of human intuition in use for centuries and more, which he has now named, and explained according to the workings of the brain.

So far, so good. He has articulated a characteristic of symmetry.

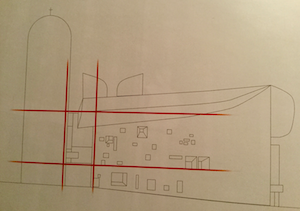

Chapel at Ronchamp, by Le Corbusier.

And yet, it is really not quite convincing. For example, his book has several images of Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp. Ruggles calls it a beautiful building, and later overlays nine squares on three façades of the chapel, which supposedly demonstrates its beauty. But Ronchamp is notably lacking in symmetry, and in stretching the nine square to fit the chapel he appears to have demonstrated its weakness as a concept. If a nine square can be made to fit the chapel, it can fit any building at all.

Ruggles’s nine square placed over chapel.

Ruggles’s book reminds me of a similar book, The Old Way of Seeing (1994), by Jonathan Hale, who applies slanted lines across Colonial houses linking important points of their design, structure and detail to illustrate proportion in façades. He writes, “Whether the designer knew he was creating the pattern is less important than that the pattern is there.” Just so. The large degree to which the pattern can be stretched to apply to so many different buildings undermines its utility as a way to identify beauty. Likewise with the nine square. Both pattern types seem too ex-post-facto to fly.

Ruggles next tackles the idea that the human face gets the swiftest and most sympthetic attention from the brain. He claims that the human face is fascinating because (to be brief) it fits the nine square. Well, maybe, but the more likely reason is that from babyhood on, people are always looking at faces, and always have, and that this, not the nine-square nature of a face, explains why they are so alluring – simply because they are faces – and why buildings whose windows and doors seem to make a face are so popular.

Zaha Hadid’s Port House addition, Antwerp.

Ruggles then strays somewhat from the nine square in order to justify a despicable modernist conceit – the value of modernist additions that contrast severely with the original traditional buildings. Since the nine square seemingly could not apply to these, which are downright anti-symmetrical, Ruggles goes back to his description of how the brain and nervous system respond to stimuli. He cites studies that find that modern architecture, with its jagged edges, is more stressful and traditional architecture, with its continuity of familiar norms, is more relaxing. In this penultimate chapter he cites, with illustrations, several of the most celebrated (by modernists) examples of this – the Libeskind addition to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and the Port House, in Antwerp, with its modernist hulk by the late Zaha Hadid placed atop a 1922 fire station. The implication, stated directly, is that ugliness is not offensive if beauty can balance out its stressfulness.

That is contrary to how people perceive architecture. A modernist building that disrupts a street’s continuity or a modernist addition to a traditional bulding both degrade the street. A place is perceived as the sum of its parts, not item by item, as if it were a museum gallery in which people look at one painting and then go on to see the next. Occasionally they do observe a street building by building as they stroll, and its continuity may be “disrupted” by a singularly attractive building or a singularly repellent one. Consciously or unconsciously they assess the impact of either intrusion – adding to or subtracting from the street’s appeal. A building that subtracts from the street’s appeal may be reliably described as poorly designed.

To justify such a subtraction, Ruggles seems to depart from most of what his book has previously argued, and states: “Fortunately, for every action there is an opposite and equal reaction.” He states it in terms of our nervous system, in which “sympathetic” (stressful) and “parasympathetic” (relaxing) design features compete. Never mind the confusion caused by the seeming inversion of meaning in these two words. The implication embraced by Ruggles is that ugliness is not offensive if it is balanced by beauty. This is simply absurd. I can hardly believe the author really believes that it holds water.

Ruggles’s book places great emphasis on the mistake modernists made when they ousted beauty from architecture. After quoting an architect from the firm of Coop Himmelb(l)au, he describes the damage this has done:

“Ugliness is the next step in the pursuit of beauty.” This attitude is being passed on in many universities most every day. I once attended a jury at an architectural school. During the presentation, one student used the word “beautiful” to describe an aspect of his presentation. The professor’s reaction: “Don’t ever use that word in this class again.” This is the attitude that we are living with. I firmly believe that no one set out to intentionally harm society. I firmly believe that they did not have the information available to properly guide us. We now do.

Yes, we now do. But Ruggles does not seem to understand it. Science is not telling us that we can enjoy both architecture that is natural and architecture that is unnatural. No. Science is telling us which architecture is attractive and which is repulsive, and why, and why we understand the difference intuitively. Ruggles seems to believe – he has many co-believers – that a compromise between the natural and the unnatural, between beauty and ugly, can be perceived as beautiful. His book says the science of neurobiology points the way to that compromise. No, it does not.

Still, the nine squares, parasympathy and all that are secondary to the truth expressed in the best prose of Ruggles’s book – even if its author does not realize it. It is that beauty in architecture is what has evolved over the broad expanse of time, shaped by the human mind following nature’s biological guidance, not the plainly idiotic experimentation of modernism’s founding charlatans and their deluded followers.

It is much more important for an author to express a deeper truth when that truth remains unjustly suppressed by many decades of cultish architectural establishment than it is to add yet another doubtful key to that deeper truth. Don Ruggles’s Beauty, Neuroscience & Architecture – subtitled “Timeless Patterns & Their Impact on Our Well-Being” – does that very important work. It, and not his theorizing about the nine square, etc., is at the center of his beautiful book. It is well worth reading.

Verrieres, Cherry Hills Village, Colorado, by Ruggles Mabe Studio. (RMS)

If I may: the glassy malformation on a 17th-century building is Hadid’s Port House, not Royal Ontario Museum.

And I wonder, if Mr. Ruggles deems this OK, will he be willing to plant a parasitic fungus on himself to balance out his own body’s God-given symmetry and order?

LikeLike

Many thanks for the heads-up, Artemas, though it appears that the parasitic fungus belongs on my head for making such a ridiculous error!

LikeLike

I’m anonymous – don’t know why my id didn’t post -Steve Bass

LikeLike

David – Thanks for this review – it supports my view that modern reductionist science will not rescue us from entrapment in ugliness. Beauty is metaphysical and, in my personal opinion, can best be approached by attempting to understand its position and nature in Platonic and Pythagorean philosophy – however this requires us to step away from materialism and functionalism; to enter a realm of symbol and analogy – perhaps a journey too far for many, even well intentioned people. Time will tell.

LikeLike

Steve, I think you are quite right. Underlying the book is Ruggles’s basic rejection of modern architecture, which arose not from his understanding of the science itself but from feelings generated by the science and its explanation of intuitive reactions to buildings, which he proceeded to explore. Not sure what to make of the nine square or his other analyses except to regret that, for some reason, he has sought to use them to help justify the modern architecture he otherwise seems to understand so well. His book is useful and admirable to the extent readers can separate its two primary aspects, one of which is highly valid and important, and the other not so much. Science helps to explain architecture’s symbolic and analogical characteristics. Ruggles’s book is strongest where it uses science to promote understanding those characteristics, and weakest when he seems to manipulate science in order to bring about what may, to him, seem a more comforting view of architecture in its harshly divided status, now well into its second half century.

LikeLike