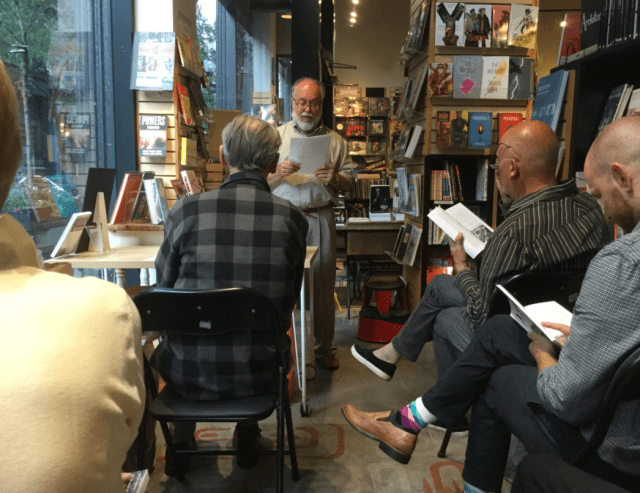

Author reads at book launch of Lost Providence at Symposium Books. (Victoria Somlo)

Last night’s Lost Providence book launch concluded with a stimulating series of exchanges regarding the nature of architecture and the allure of cities. I mentioned the work of mathematician Nikos Salingaros at the University of Texas at San Antonio. His theories, as I usually describe them, tie the high popularity of traditional architecture to primitive mankind’s survival needs, which included the capacity of the primitive mind to “read” the details of the surrounding environment. Such interpretation was needed to find dangers lurking in the savannah – such as a hidden tiger revealed by its shadow on a nearby rock. Not noticing that in time might conclude the life of the cave man. Fortunately for him (and us), his brain developed the ability to intuit the meaning of signs in the wild. Today, our intuition and our subconscious register that type of information as complexity in our built environment. Traditional architecture is a far more complex aesthetic phenomenon than the “purity of line” favored in abstract modernist architecture.

That’s an expanded version of my answer to a listener’s question. Some who attended at Symposium Books might have thought I had leapt off the deep end. But no, this is one of the most promising segments of emerging science. Salingaros, who has worked closely for decades with architectural theorist Chrisopher Alexander, recently published an essay summarizing the threads of this emerging science in Conscious Cities Journal. I’ve plucked three interesting paragraphs from “How Neuroscience Can Generate a Healthier Architecture.” Readers should read the entire essay. They might also want to click on the Wikipedia entry for conscious cities.

Healing environments are reminiscent of but don’t need to copy vernacular architecture. Design techniques that adapt to our neurophysiology necessarily bring us to appreciate design and tectonic solutions from our own past often swept away by industrial modernism. We do not advocate returning to older practices out of nostalgia, but instead urge their re-discovery in a new, ultra-modern context. The rewards of adopting healing design tools without ideological prejudice against the past are going to be profound. …

Salingaros is arguing that there are benefits to design practices that evolve over centuries of trial and error, where the latest “best practices” are handed down by successive generations of designers and builders. And there are negatives to design practices that are “experimental,” in that designers create buildings by using patterns and techniques that are not only different from historical designs but from the designs of their own rivals today. To humans, the benefits of the traditional method, briefly stated, are called “health” and the negatives of abstract creativity are “illness.”

In the next paragraph, Salingaros refers to the difference in speed with which the brain responds to traditional stimuli versus experimental “creative” stimuli. The latter, in which abstraction clashes with experience, is harder to understand, and thus the brain perceives its meaning more slowly (if at all).

This cognitive phenomenon is reminiscent of schizophrenia and results from conditioning. Abstract design exercises instill a subconscious preference for industrial forms, non-convex spaces, textures, and materials of industrial modernism that normally alarm us. Post-war architectural training superimposes a liking for negative valences, opposite to our evolution. Taking advantage of neuroplasticity, the Bauhaus teaching method engages a person emotionally and physically by using the tactile sense and exercising one’s muscles. Those kinesthetic exercises re-wire students’ brains to ignore bodily signals (our visceral response to structures), and replace them with intellectualised abstractions. Making compositions and building studio models with an empty, unnatural shape teaches students to judge according to style and ignore conflicting valences. …

Here is Salingaros’s conclusion:

Neuroscience opens a path to a new kind of adaptive architectural practice that can measurably increase human well-being. Many of the components necessary for this new design discipline are already in place, and others are being developed. We still need to solidify existing results on how the environment affects our body and health, and complete this program with research that explores new directions. Bringing together different groups of researchers who are all pursuing the same goal will strengthen the results, and help to forge a major new global discipline. The “Conscious Cities” group is making such an effort.

Good!

I actually posted on that here:

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think this essay is relevant!

– The Mental Disorders that Gave Us Modern Architecture: http://commonedge.org/the-mental-disorders-that-gave-us-modern-architecture/

I just made a photomontage from the “stabbur” of my great grandfather today, finished in 1920: https://permaliv.blogspot.no/2017/09/stabbur-grythengen-1920-even-helmer.html

LikeLike