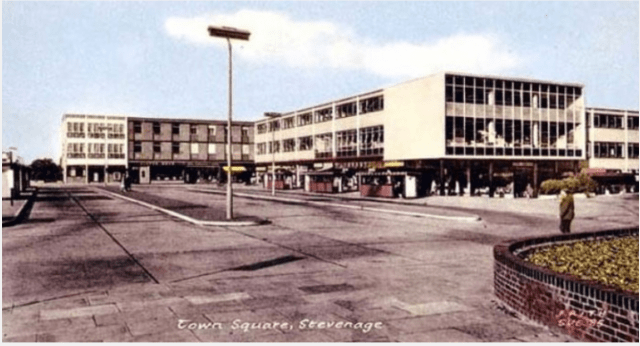

Parcel 2 proposal offered by Urbanica and approved by state office of preservation (!). (RISHPO)

New and dubious projects (the only kind permitted in Providence, it seems) have crossed my desk, perhaps belatedly. One is for an 11-story residential building in the Jewelry District, appalling in its design as is apparently now mandatory under official city and state design directives, and the other is for a five-story building on Wickenden Street, in Fox Point. News of the latter comes to me from Providence Monthly and William Morgan’s April column in GoLocalProvidence.

Also, courtesy of the Providence Preservation Society’s advocacy update, comes news of the latest version of the apartment complex slated for Parcel 2 (above), which obeys the city design mandate noted above. The City Plan Commission offers a lengthy description. The link includes dozens of images, and I’ve taken my best guess as to which offers the clearest idea of what is likely to be built. As you’ll see, it was not easy.

Here is the dubious proposal for Parcel 14, in the Jewelry District, or Innovation District, or whatever it is called these days:

Proposed residential tower on parcels 14 and 15 in Jewelry District. (CV Properties)

The proposal for a five-story residential building (pictured just below) would be built on the south side of Wickenden and east of Brook Street. It would replace a bland building whose loss would be regrettable only to the extent that the proposed building ignores the character of Wickenden. It does, but possibly less so than recent additions to the street. Who knows what it will look like once what is approved becomes what is built? (This is called damnation by faint praise.)

The proposed design for a residential building at 269 Wickenden Street. (Providence Architecture Co.)

Still no movement on the new version of the Duck & Bunny, whose owners promised to rebuild it after they tore it down on Easter weekend of 2021.

The photo below of Sheldon Street, a block north of Wickenden, comes from Will Morgan’s excellent GoLocal review of the situation in Fox Point, and serves to remind people of what a typical Providence residential street looks like. This photo is an error, originally described by me as Wickenden Street; but it is not much different in some stretches from Sheldon. To replicate such historical character should not be difficult. In the case of 269 Wickenden, there is plenty of room in the rear to build apartments to make up for what ought to be improper to build along Wickenden. But people have to know what historical character is, and whether they really want to preserve it.

Wickenden Street, in Fox Point, showing historical character. (William Morgan) Actully, this is Sheldon Street. Sorry!

Providence Monthly reflects the establishment view of the city, although publishers Barry Fain, Richard Fleischer and John Howell are unlikely to be pleased with that description. The articles in PM suggest that the adults have left the building, with only fashionistas to take their place. Many articles show little understanding of why Providence is a great city or the forces that place it at risk.

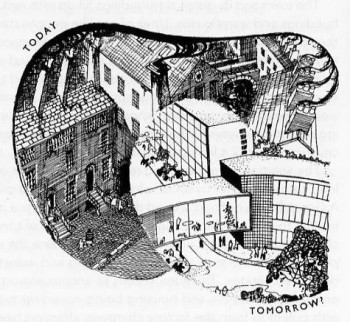

For example, in its “Hot Topics” section, after describing the 11-story building proposed for Parcel 14, plus other recent and planned projects, mostly appalling, in the Jewelry District, the neighborhood association note from the Jewelry District reads that “the future never looked brighter for the Jewelry District.” Plasticky generic architecture is the law of the land. Of course, the leaders and staff of every city and state body overseeing these developments are modernists (though, again, they’d be reluctant to admit it). Modernism may be fine in its place, but that place is not a city that thrives on its historical character. These “experts” are trained to hold historical character in contempt, and to see what most people love as a bulwark against what the experts consider “progress.” Every hearing before these bodies is an exercise in trying to appear friendly to historical character without revealing their true colors.

Another example from the same source – an organization I’d had high hopes for – the Mile of History Association, which supposedly protects Benefit Street (where I lived for 14 years in 1985-1999) from attacks against its voluminous historical character, reads: “MoHA is also pleased to report the restoration of the streetlights along Benefit Street is complete. The new lanterns look similar to the old ones, but cast brighter, whiter light … .” In short, this is not restoration but modernization, replacing the soft amber glow of the old lamps with a filament of white glare. All of Benefit Street will rue this attack on their neighborhood’s gentle ambiance.

In the same section, the headline for the note from the Fox Point Neighborhood Association reads: “Fox Point residents fight for their neighborhood character.” Here Providence Monthly takes a different tack in reporting on the proposed Wickenden Street building. The left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing: “This proposal could forever change the environment and sensibility of what it means to live in a small, historic community.”

But neighbors throughout Providence do not seem to know what that means. Opponents of projects, even including the mercifully defunct Fane tower, have voiced a willingness to put up with the sort of “generic” design that is eating away at the city’s character. Most opposition groups in Providence do not understand that preserving the historical character does not mean refusing to move into the future.

This false attitude is that of the staff of the City Plan Commission and other panels that neighborhood preservationists should be able to rely on. It is taught in architecture and planning schools throughout the country. And those whom elected officials appoint and hire for those commissions and agencies directly and actively oppose the sentiments of voters who put those elected officials into office.

Too bad this anti-preservationism is also taught, with occasional accidental ventures into sanity, to readers of Providence Monthly. Its publishers – especially Barry Fain, who was once the sole sane voice on the Capital Center Commission’s Design Review Committee – should know better.