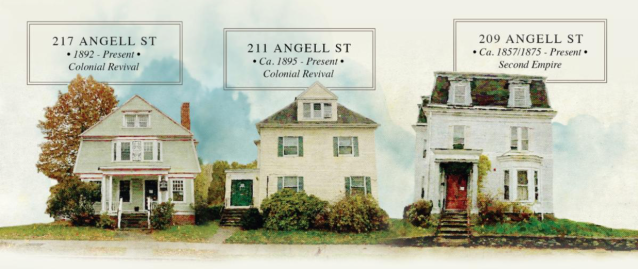

Three houses on Angell Street, in Providence, whose proposed demolition is considered mysterious.

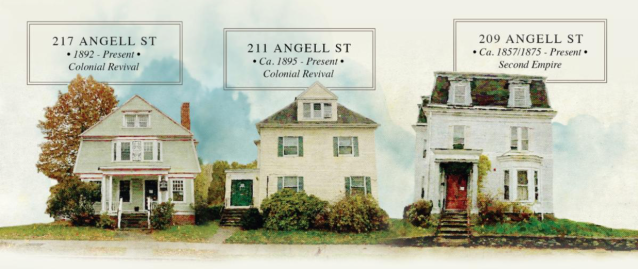

Recent photograph of the three vacant houses whose demolition may be imminent.

Someone has it in for a row of decent old houses on Angell Street. Specifically, they are Nos. 209, 211 and 217. They should be preserved. Their preservation should be second nature at every level of policy in Providence. Yet demolition permits are, according to the Providence Journal, in the works for all three – no one seems to know who applied for them, or for what purpose – and so the houses are sitting ducks awaiting their sad fate.

The three were purchased by 217 Angell Investments II LLC on Oct. 4 of this year for $4.5 million. The firm was registered with the city on Sept. 13. The location had been chosen, according to city records and a report by WPRI Channel 12 News, as the site for a six-story Smart Hotel, with 116 rooms and internal parking for an unstated number of vehicles. Two attempts to develop a hotel were blocked in 2020 and 2022. No proposals have emerged as a possible replacement. … Yet.

Mayor Smiley’s spokesman, Josh Estrella, told Channel 12:

The owner of this private property requested this demolition and has followed all of the necessary processes required by our zoning ordinance. … The City of Providence has a robust process for preserving historic landmarks, however, these properties are not in a historically protected zone.

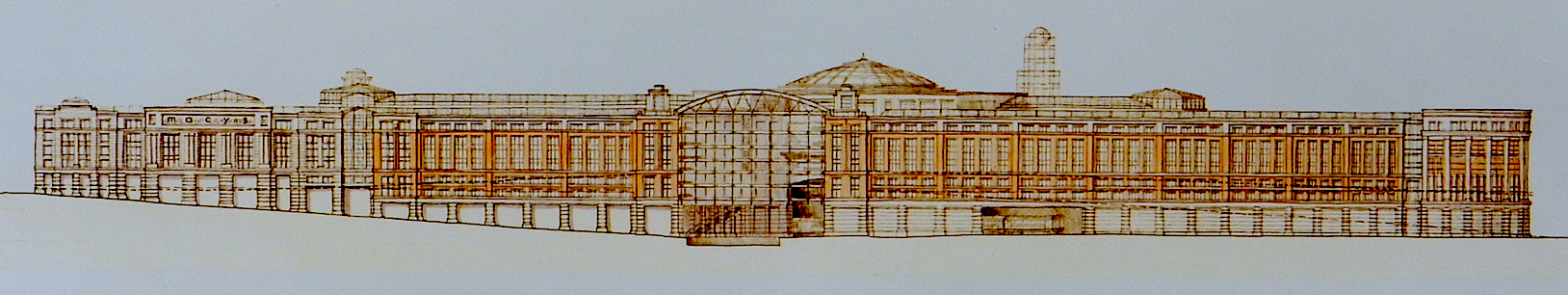

None of the three is listed in the 1986 Citywide Survey of Historic Resources by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, published in 1986. The illustrator whose nice work sits atop this post is unidentified and unknown to me. Beneath it is a recent photo, artist also unknown. The drawing lists them as Second Empire, Colonial, and Colonial, respectively, built in 1857-75, 1895, and 1892. None of them is an extraordinary example of its style of design. They are all pleasant houses of relatively modest historical and architectural merit in the College Hill/Thayer neighborhood. They are deemed to be “contributing” to their district (in the planning vernacular). There is no particular safety provided for these houses by the status of their district, which is not an official historic district, and even if it were, the protections offered would be minimal.

They are historical houses in the sense that they were built “back in history,” but they are not officially “historic” because there is nothing in their architecture or in broader slices of their history that puts them on the map, as it were. But as “contributing” houses their sheer abundance helps to make Providence the beautiful city it is, with a historical character that is the city’s most valuable attribute.

(That big blue office building off Waterman Street south of Thayer a couple of blocks from the three targeted houses, curiously known as “Bliss Place,” is, I believe, a “noncontributing” building. That’s not just a belaboring of the obvious, it is an understatement of considerable significance. Its very existence stinks up the place. Bliss Place indeed! If Providence had sensible planning, the planners would target 245 Waterman St. for demolition and replacement with something more attractive – except that’s too low a bar.)

The easternmost of the three houses slated for demolition, and the most attractive, is the office of the Bishop Group, whose 2023 and previous “free” calendars for customers sit atop a stack of papers on a stool next to my desk. Ed Bishop is my insurance agent, has been for decades. He is still a friend (I think!), though I have criticized previous development proposals of his, and certainly oppose this demolition – if he has anything to do with it, which has not been officially declared, and which I don’t assume or know for sure, and which mystifies the journalists covering this story (including me). Today all three of the houses are vacant.

The new owners have the right to destroy these houses if they want to do something else on the land, such as build a hotel, assuming that the envisioned use is legal under the zoning of the district. The recently re-elected councilman for this Ward I, John Goncalves, was present at a vigil for the three houses sponsored by the Providence Preservation Society. and had several things to say to reporters (I was not there).

Goncalves wrote and passed legislation that forced the city to inform neighbors that demo permits were being processed for the three houses on Angell. Otherwise, he said, these houses could be demolished “in the darkness of night, on an Easter Sunday,” as occurred on Easter weekend of 2021 when the beloved Duck & Bunny building was suddenly razed on Wickenden Street. He added: “Neighbors need to be briefed and not blind-sided, waking up only to discover a hole in the ground and an empty lot in their neighborhood and community. This is unacceptable.”

Goncalves told the Brown Daily Herald that “with no development plans in place, the demolition and subsequent empty lots here will leave a massive hole and scar in this neighborhood. … Demolition of these properties in these housing units with no plans is a travesty to the community, especially in light of the housing crisis that we face.”

Yes, the owners have their rights, and property rights are important, but the city has a duty to protect the rights of citizens at large, which are enumerated, as far as property and land use are concerned, in the Providence zoning code and comprehensive plan. These documents, made with input from citizens, not just politicians, consider the city’s status as a historic city, a consideration that bears on the value of its historical character. Part of that value is economic, and thus protects aspects of the city that enable it to compete with rival cities that may have been less successful in protecting the historical character they inherited, and which thus lose a considerable amount of business and tourist trade, and have done so over many decades, some of which loss has accrued to the benefit of Providence.

But the zoning and planning functions of the city also protect, or ought to protect, its beauty, not just as a boon to its economy but as an asset for all citizens which they may enjoy freely as citizens. While the city has done a good job protecting its historical character (and thus its beauty) for centuries – indeed, its historic character was not at risk until after modern architecture came into vogue in the 1950s. And since then the city’s dedication to its beauty has flagged, and the rights of every citizen are at risk.

Goncalves was wrong if, in his conversation with the Brown Daily Herald, he was suggesting that the absence of a plan to replace the three houses is why their demolition – they are still up as of today, surrounded by a chain-link fence – would be “a travesty.” No, the travesty is in their destruction, not in the absence of a replacement plan. The travesty would be diminished only if a plan to replace them with buildings of equal or greater beauty had been proposed. Such a prospect is intensely unlikely – not because such a prospect is commercially infeasible but because the minds of Providence planning officials are, and have been for decades, so dim. They are, as it were, stuck in the past. If Goncalves understands this, he has get to make it known to his constituents at large. (He should let me know if I am wrong about that.)

Saving the three houses on Angell Street is part of the way citizens can protect their rights, presumably with the help of elected officials. If elected officials do not think it proper to go to bat for these three houses, they will be demolished and the fight to protect citizens and their rights will continue, either there when a proposal finally emerges, or at other locations, where they may succeed or not. But even if they fail they will slow down the assassination of beauty in Providence. Its prosperous future, if it is to have one, depends upon its beauty.