View of Old Stone Square (1984) from Turk’s Head Building (1913), site of author’s Turk’s Head Club luncheon with Journal publisher Michael Metcalf in 1984. (Photo by author)

View of Old Stone Square (1984) from Turk’s Head Building (1913), site of author’s Turk’s Head Club luncheon with Journal publisher Michael Metcalf in 1984. (Photo by author)I decided to go with Chapter 19, “We Hate That” because how could you tease readers with such a headline and then go with Chapter 18, “Capital Center Plan”? Well it would have been wrong. So this is the first half of “We Hate That,” and let’s get right to it to find out what “that” might be, as if one could not guess from the photo above, not to mention if not if not from foreknowledge of my own hatred for a certain building – overtaken, in time, of course, by the GTECH building.

***

In the fall of 1984, I was standing next to Michael Metcalf, publisher of the Providence Journal, at a window looking east toward College Hill from the Turk’s Head Club, on the eleventh floor of the Turk’s Head Building, erected in 1913. It was the day Metcalf offered me a job on the newspaper’s editorial board. He pointed out the window and, in his gentle voice, said, “We hate that.”

I did not need to be told what “that” referred to.

It was Old Stone Square, newly erected by the development arm of Old Stone Bank and designed by celebrity architect Edward Larrabee Barnes of New York. Metcalf pointed at the eleven-story square building looming against the backdrop of College Hill, with big square spaces cut out of its huge square mass from the lobby entrance and from the opposite upper quadrant of the building. It stuck out like the proverbial sore thumb. It did not start out this way. It was originally to be a pair of shorter buildings flanking a plaza, through which would be visible the dome of the Old Stone Bank. Its look was to have been postmodern, somewhat squishy but identifiably traditional, even Georgian. Its key defect in the eyes of its leading opponents, however, was to mask views of all but a sliver of historic South Main Street as seen from corporate suites on the upper floors of downtown towers across the river.

The Providence Preservation Society, by then a recognized pillar of the city’s business establishment, vociferously opposed the initial postmodernist design but, after some Old Stone pushback and a redesign of the building, became more ambivalent.

David Macaulay, an author and illustrator of books on architecture, spoofed the design in a cartoon published on June 13, 1982, in the Providence Sunday Journal, riffing off Old Stone’s new corporate brand, Fred Flintstone.

Mayor Cianci stepped in to negotiate a compromise, which involved the new design by Barnes. The result was not as wide but much taller than the two buildings of the original design. It sits on the southern half of the lot with a park on the northern half. It did not hide as much of South Main Street’s historic frontage as the original proposal, but it was starkly modernist. Squares of light and dark gray gridded its square façades, not unlike the pattern on a box of Ralston-Purina cat chow. Why suddenly such an angry confrontation with its historical context? It seemed to me that a desire on the part of the Old Stone rainmakers for revenge against the preservationists might have been part of the answer.

In 1999, after years of failure to ferret out an admission of revenge as a factor in the design of Old Stone Square, I visited Old Stone’s lead developer, Scott Burns, at a café in the Chelsea district of London. He, too, refused to confirm my suspicions, and I have allowed them to fester undisturbed ever since.

And yet, the years following Old Stone Square’s erection saw an efflorescence of new traditional architecture that seemed to come out of nowhere. It did not come out of nowhere. I cannot pinpoint the wellspring of this shift, but I can point to evidence of its appearance on the Providence stage.

Old Journal Building (1908) covered in modernist faux facades circa 1955. Originally a J.J. Newberry Co. atore, thereafter a Thom McAnn shoe store. (Providence Public Library)

Old Journal Building (1908) covered in modernist faux facades circa 1955. Originally a J.J. Newberry Co. atore, thereafter a Thom McAnn shoe store. (Providence Public Library)Strong hints of a reaction against the modernist conceits of the downtown Providence 1970 plan and the College Hill study came one after another in the 1970s and 1980s. The mayor’s Office of Community Development instituted a program to finance small projects, such as helping building owners remove faux modernist (“ugly is just skin deep”) façades erected in the 1950s and 1960s, especially along Westminster Mall, the Old Journal Building being a prime example. The Providence Preservation Society expanded its attention to preserving historic fabric throughout the city, but focused even more on downtown. Mayor Cianci joined preservationists and the business community to ensure that the Wilcox Building – one of the grand dames of Weybosset Street – was restored after a fire in 1975. Cianci, Outlet chief Bruce Sunlun and publisher Metcalf of the Journal managed to resuscitate the Biltmore Hotel (1922) in 1979 after three years of closure. Cianci also led an effort to block the demolition of Loew’s Theater (1928) and then to restore it as the Providence Performing Arts Center. The Majestic (1917) was renovated as the Lederer, a live venue for the Trinity Square Repertory Company.

Wilcox Building, center, was restored after a fire in 1975. See Arcade at left. (Author’s photo)

Wilcox Building, center, was restored after a fire in 1975. See Arcade at left. (Author’s photo)The Arcade (1828), which had almost been razed in 1944, was purchased by Gilbane Properties and restored in 1980 by Irving Haynes, who had just restored City Hall and was present for the famous napkin doodle of 1981. Johnson & Wales College started buying and fixing up old buildings for its widely dispersed downtown campus, including the Burrill Building (1891), long the Gladding’s department store. Paolino Properties, after demolishing the Hoppin Homestead Building, turned from whacking old buildings for parking lots to renovating old buildings for new and more hopeful pursuits. In fact, despite their good works, J&W and Paolino Properties vied in the public mind for the role of “evil landlord,” alleged nefarious owners of the entire downtown.

Mayor Cianci, who died in 2016, may be the most controversial figure in Providence’s history since Roger Williams, or at least since Thomas Dorr. His two administrations straddled a 1984 conviction for assault. Still, he would kiss a pig for a vote, attend the opening of an envelope and was tops at talking up Providence or locating hidden pots of money for this or that project. And yet, the civic renaissance gathering steam during Cianci’s second administration (1991–2002) made progress as much in spite of as because of his leadership. Keeping Cianci’s hand out of a project’s pocket made already complex developments harder to manage politically. His reputation alone probably kept some entrepreneurs from investing in Providence. his shady dealings, suspected by many, emerged only during his 2002 corruption trial, where he was convicted of conspiracy, a single count among a score or so of charges. It may be fair to say that, in spite of his professed love for the city and his adept cheerleading for its revival, he hurt it as much as he helped it.

But as the city entered the 1980s, all that was in the future.

Vincent A. “Buddy” Cianci Jr., mayor, 1975-1984, 1990-2002, with and without his famous “rugs.” Lower left, Cianci gestures to “his city” in iconic photograph.

Vincent A. “Buddy” Cianci Jr., mayor, 1975-1984, 1990-2002, with and without his famous “rugs.” Lower left, Cianci gestures to “his city” in iconic photograph.***

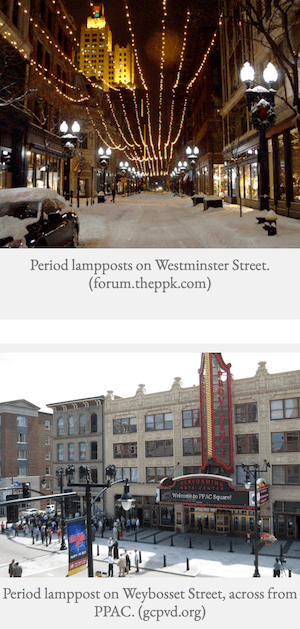

And the next post, the remainder of Chapter 19, “We Hate That,” will describe the buildings and civic architecture saved and restored in the 1970s and ’80s, including Westminster Street, which was beautifully renovated by Mayor Paolino in the late 1980s.