Porter Garden Telescope from Telescopes of Vermont (Russ Schleipman)

Years ago I was wandering through a naval equipment store in Provincetown, on Cape Cod, and found a telescope of high quality and elegant appearance. It was too pricey for me, $500 or so. I wanted something through which I could spy on downtown Providence from my fifth-floor loft in the Smith Building, right behind the Plunder Dome – City Hall – whose offices were a target. Or to watch people strolling on that sliver of new waterfront visible to me at the base of College Hill, some 980 yards straight down Fulton Street from my aerie. My wife gifted me a lovely brass telescope that, alas, looked better than it worked. It always sat next to one of the windows in our loft, but for actual snooping I had to make do with a set of binoculars.

Today, I’d rather own a Porter Garden Telescope, designed in 1923 by Russell Porter, of MIT. I have a garden to put it in now, or rather a backyard. (It was a garden when we bought the house; now it is a backyard.) It is definitely not for peeping down from a lofty apartment at the cutie disrobing in her apartment on the west slope of College Hill. (I hasten to add I’ve never seen one of those.) It is for looking at the heavens – the planets, the moon, the stars.

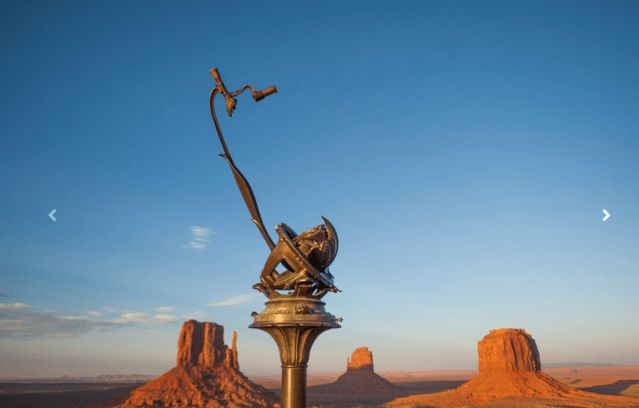

But though it would grace our backyard – turning it back into a garden in one fell swoop – it belongs in the Louvre. (An original now sits in the Smithsonian.) It hasn’t the slightest resemblance to the Platonic idea of a telescope. Recently at a party in Boston sponsored by the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, I met Corina Belle-Isle (a name that also belongs in the Louvre). She represents Telescopes of Vermont, a firm in Norwich there that makes and markets the Porter reproductions, which she described to me, as it won last year’s Bulfinch award in the category of craftsmanship/artisanship.

Russ Schleipman, the president of Telescopes of Vermont, has written:

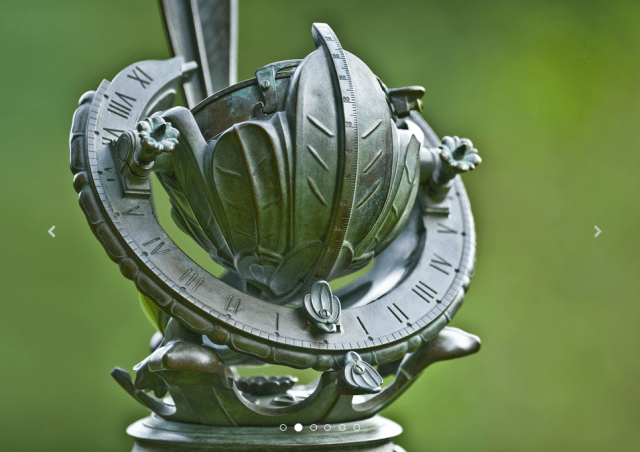

[T]he Garden Telescope was conceived as a superb optical instrument, Art Nouveau bronze sculpture, and working sundial, all in one. It was a model for the 200 inch Hale Telescope at Mt. Palomar in San Diego, and thereby found its way to the Smithsonian. Decades later my father, Fred Schleipman of Norwich,Vermont and the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, driven by a deep passion to do so, organized a talented team for the express purpose of resurrecting this unique instrument, adding superb modern optics and considerably enhanced functionality.

He adds:

Though it is a reflecting telescope, the familiar tube is absent. Instead, a bronze leaf holds the optics. They lift out in seconds, leaving a graceful sculpture and working sundial which can be permanently installed outdoors as a distinctive centerpiece.

Each telescope requires 400 hours of labor to produce, and so I can imagine that each of the production run of 200 copies will boast the slight differences that set this bronze reproduction apart as an act of craftsmanship. Here is a more technical description of the telescope, which is 66 inches tall (including its pedestal) and weighs 110 pounds:

A six-inch mirror and eyepieces of 50 and 75 power deliver the moon, Jupiter and its moons, and Saturn with great detail. Currently there are thirty six in the world. The telescope, pedestal and optics case (made by a maker of cases for fine London and Belgian shotguns) comprise the kit, which sells for $65,000 US, plus delivery.

So now I have a garden but I still lack $65,000 – the price, and a fair one. It would make a fine Christmas gift, and a savings, for those out there who last year gave their loved one a Lamborghini with a ribbon on top. Yet, as a work of art, to see photographs of it serves as a gift in its own right, which I am happy to convey to my readers in their hundreds and thousands. Merry Christmas and happy holidays!

***

The first shot below is Vermont Gov. Hartness peering into the eyepiece of the telescope. Below are images from the Telescopes of Vermont website, which includes an elegant video of Russ Schleipman explaining the operation of his advanced reproduction of the original.