Among the platitudes of architecture these days is the modernist credo that innovation is the chief merit of the building arts. Innovation is important, but modernists have a narrow definition of the term that limits their vision. John Ruskin, the 19th century British art critic, saw this clearly long before the advent of modernism as a force in architecture, under the influence of which almost the entire field abandoned traditional concepts of beauty.

Here, grabbed from Architecture in America: A Battle of Styles (edited by Henry Hope Reed and William A. Coles), is a passage from his “Two Paths” address to architects in 1857:

If you … can get the noise out of your ears of the perpetual, empty, idle, incomparably idiotic talk about the necessity of some novelty in architecture, you will soon see that the very essence of a Style, properly so called, is that it should be practiced for ages, and applied to all purposes; and that so long as any given style is in practice, all that is left for individual imagination to accomplish must be within the scope of that style, not in the invention of a new one.

… Let us consider together what room for the exercise of the imagination may be left to us under such conditions. And, first, I suppose it will be said, or thought, that the architect’s principle field for exercise of his invention must be in the disposition of lines, mouldings, and masses, in agreeable proportions. Indeed, if you adopt some styles of architecture, you cannot exercise invention in any other way. And I admit that it requires genius and [a] special gift to do this rightly.

John Ruskin in 1863. (Wiki.)

It seems to me that Ruskin is on target here. He was urging his listeners to find new ways to apply old rules with greater virtuosity and an even more pleasing effect than had been achieved by their predecessors. Such an attempt may be beyond the comprehension of most modernist practitioners today, and modernist theorists no doubt seek to keep the idea very well hidden, especially from students. Ruskin’s thinking was notoriously complicated, whether in architecture or the many other fields in which he worked his mind. But it beats me how he can have leapt to the above sublimity from the following inanity, written when Ruskin was younger, in The Stones of Venice (1851-53). It is also taken from Architecture in America. Here it is:

[T]he whole mass of the architecture, founded on Greek and Roman models, which we have been in the habit of building for the last three centuries, is utterly devoid of all life, virtue, honourableness, or power of doing good. It is base, unnatural and unholy in its revival, paralyzed in its old age. … The first thing we have to do is cast it out, and shake the dust of it from our feet for ever. Whatever has any connxion with the five orders, or with any one of the orders, – whatever is Doric, or Ionic, or Tuscan, or Corinthian, or Composite, or in any wwise Grecized or Romanized; whatever betrays the smallest respect for Vitruvian laws, or conformity with Palladian work, – that we are to endure no more.

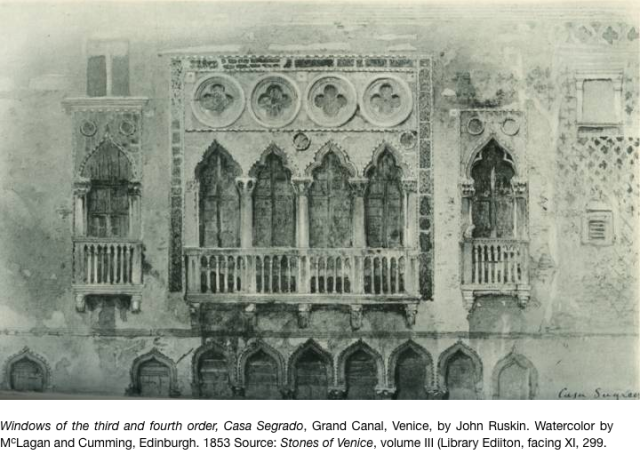

Hard to figure. Very hard to figure. Ruskin’s book on Venice is widely associated with a preference for the Gothic over the classical as better reflecting what Salvatore Settis, author of the recently published If Venice Dies, calls the “soul” of Venice. Ruskin likes the idea of preserving old buildings but believes that the signs of aging and decay should be preserved with them – an idea I find immensely attractive, and to a degree responsible for the allure of such U.S. cities as New Orleans and Charleston.

And yet Gothic architecture makes extensive use of ancient forms. H.P. Lovecraft also involved himself in the sort of critical minutiae that enabled him to love Georgian buildings and hate Gothic ones. In letters to the Providence Journal he expressed his admiration for the proposed new Providence County Courthouse that was to replace the old Gothic one. Today, one can only envy him the narrow palette of his likes and dislikes. One must cringe at how Lovecraft – or Ruskin, for that matter – would react to the sort of modernism that has left Providence with Old Stone Square and the GTECH building!

Well one reason is that what has been mostly perpetrated since 1950s makes all earlier styles a thankful relief. Them to cite Perter Blake’s “Form Follows Fiasco” (1978) and “God’s Own Junk Yard” (1979) and these from one of the early apologist for the International style modernism.

LikeLike

I have always admired Ruskin as a superb writer, perhaps the best who has ever written about architecture in the English language, and yet what he has to say is almost entirely nonsense. He will occasionally come out with something stunning and obviously true, followed by some inanity like your second quote. He was a man of fierce attachments and equally fierce rejections. While no one could surpass his description of the facade of the Basilica San Marco in Venice, his understanding of gothic architecture is severely limited, if also very idealistic. On innovation and style, however, I think he’s right. Real style emerges from ways of building and these do not change so often, or rather they can’t change with every project, which is why the failure rate among modernist buildings is so high. If each one is a unique experiment, the odds of it being a failure are pretty high. Hence, there is no modernist vernacular and no modernist historic district.

LikeLike

I have always wondered, Steve, how people of that era could have such violent likes and dislikes over styles that from our perspective are all so intrinsically cherishable, with some of course being performed better than others in the whole range of styles, but all worthy of respect. And how is it that the flaws you point out that make modernist buildings more likely to fail – and the evidence for that likelihood – how is it that nobody in the profession ever seems to notice or care?

LikeLike