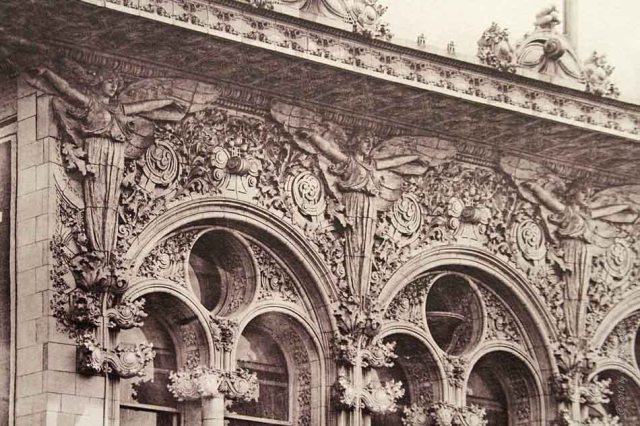

Louis Sullivan’s Guaranty Building, in Buffalo. (archhistdaily.wordpress.com)

Am plunging into a 1956 softcover copy of Louis Sullivan’s The Autobiography of an Idea, first published in the early ’20s. The introduction to this edition by University of Illinois architecture professor Ralph Marlowe Line, written with the well-known forward by Claude Bragdon, an architect and proponent of “organic architecture,” in mind, or so you would think, is a textbook example of the omission of fact on behalf of theory.

Louis Sullivan (biography.com)

Bragdon notes that Sullivan’s buildings were highly embellished, although not in the classical line. Bragdon notes that for Sullivan, “function determin[ed] form and form express[ed] function,” adding with no hint of reproof that over a building’s structure “he wove a web of beautiful ornament – flowers and frost, delicate as lace and strong as steel.” This was in 1924.

Line, writing three decades later, ignores this fact unshamefacedly in discussing Sullivan’s conviction that “no architectural dictum or tradition or superstition or habit should stand in the way … of making architecture that fitted its functions – a realistic architecture based on well-defined utilitarian needs.”

Line forgets (even if the actual Sullivan did not) that utilitas forms part of the triad, with firmitas and venustas, that has been followed by architects since Vitrivius (and long before). Nowhere in Sullivan’s famous lines on “form ever follows function” does he excoriate decoration. His preferred decorative pallette paid little heed to classical precedent, but there is nothing in his writing that is honestly translatable into “form follows function only by excluding ornament.”

In his architectural practice, he often gave himself the ornamental work and left building structure to other office members. In the hagiographies of his appointment as “precursor to modern archtiecture,” written by modernist historians, Sullivan’s pr0clivities as a professional, when discussed at all, are spoken of sotto voce or covered up altogether.

Now “form follows function” is about all that remains of the popular legacy of Louis Sullivan. As a statement it is simple and unobjectionable. As an expression of modernism’s “ornament is crime” philosophy, it is strictly hogwash. Those who know nothing of Sullivan but his association with that one entirely misunderstood phrase, and who then look for and observe any building designed by him, are bound to be baffled.

This is no surprise. Confusion is the second commandment obeyed by all adherents to the cult of modern architecture: Thou shalt not permit clarity to expose the obtuseness of modern architecture. (Awareness of this modernist abhorrence of simplicity and clarity characterizes Steven Semes’s New Criterion essay, linked in my post “Semes on Paris and our cities” last night.

Andrés Duany’s effort, through his Heterodoxia Architectonica treatise under construction, to (among other things) recapture the rep of Louis Sullivan as a classicist – that is to say, a sane architect interested in the marriage of beauty and utility – is a project whose time came long ago.

So, for the holidays, I offer some shots I took in 2013 of the entrance to Sullivan’s Carson Pirie Scott & Co. Building. Best of the season and good cheer to all of my readers, every one!

Pingback: The sources of modern silliness | Architecture Here and There