One of my favorite books is A Mencken Chrestomathy, H.L. Mencken’s own favorite essays by himself (a chrestomathy being a selection of choice literary passages, often intended to teach a language). Reading Mencken, who wrote for the Baltimore Sun in the first half of the 20th century, is a great way to learn English. A young person wanting to be a journalist should not go to journalism school. No. Instead, wallow daily in the prose of the Sage of Baltimore. Save a lot of money. The ability to call someone like the 19th century sociologist Thorstein Veblen “a geyser of pish-posh” will certainly get them a job.

On Wednesday afternoon I read a 1957 essay in Harper’s by another hero of mine, the late classicist Henry Hope Reed. In it he mentions Veblen, whose Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) discusses “conspicuous consumption” – the idea that people with more money than they need tend to spend it on things they don’t need. Mencken had fun with it in his essay “Professor Veblen,” first published in his Smart Set magazine in 1919 under the title “Prof. Veblen and the Cow”:

If one tunneled under [Veblen’s] great moraines of discordant and raucous polysyllables, blew up the hard, thick shell of his almost theological manner, what one found in his discourse was chiefly a mass of platitudes – the self-evident made horrifying, the obvious in terms of the staggering.

The last line in that essay explains its Smart Set title. In heaping ridicule on Veblen’s supposed astonishment that homeowners hire men to mow the lawn rather than keeping cows to perform the task, Mencken concludes: “Had he ever crossed a pasture inhabited by a cow (Bos taurus)? And had he, making that crossing, ever passed astern of the cow herself? And had he, thus passing astern, ever stepped carelessly, and—-”

Priceless.

I am sure that Henry Reed, ensconced among the pillars and pilasters of Heaven above, will not mind sharing space in this column with Mencken. Reed’s essay “The next step beyond ‘Modern’ ” in the May 1957 issue of Harper’s, in accounting for the rise of modern architecture, also cites Veblen: “His well-known praise for the backs of buildings as against their decorated fronts, which he considered samples of ‘conspicuous consumption,’ carried weight with a people caught in a depression.”

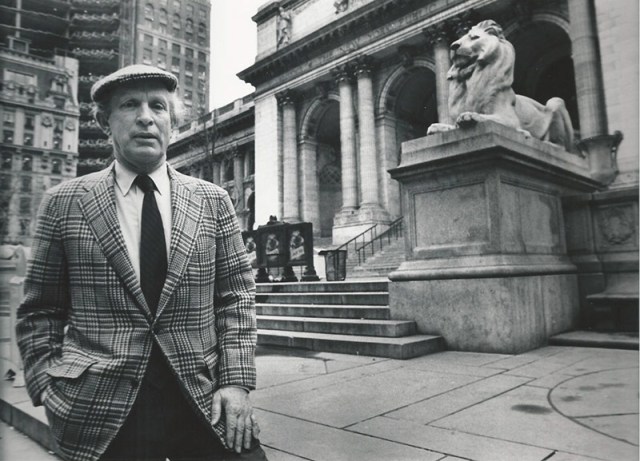

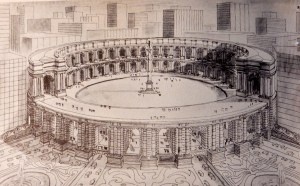

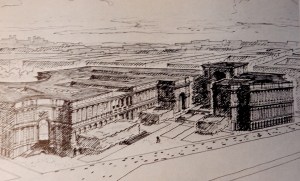

On Saturday, Reed and his legacy – including his pathbreaking defenestration of modern architecture, The Golden City (1959) – will be the subject of a symposium addressing “The Future of the Golden City” at the Franklin Inn Club in Philadelphia. The symposium on Reed, who died in 2013, is sponsored by the city’s chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. The ICAA arose from what may have been the first organization of its kind, Classical America, founded by Reed in the 1968.

As a young man, Reed went mano a mano with Ada Louise Huxtable, later the New York Times’s first architecture critic, over what buildings to feature on walking tours by the Municipal Art Society. The tours were a big hit, but Reed’s vigorous animadversions against modern architecture raised eyebrows even at the society, which eventually started sending spies to “monitor” his “rants.” A Talk of the Town by The New Yorker’s Brendan Gill accompanied Reed on a tour of Lower Manhattan and poked relatively gentle fun at Reed’s crusade against modern architecture, but readers with an ounce of good taste no doubt stood with Reed against Gill.

Around this time, an introduction by the editor at Harper’s (who styles himself “Mr. Harper”) to a piece by Reed in the March 1958 issue shows what he was up against in those days. Citing Reed’s “position that classical architecture is the only kind worth a damn,” the editor assumes “that readers who reject his views will at least enjoy his enthusiasm” – as if readers’ preference for “the Modern” was to be taken for granted.

In spite of this evidence that the deck was stacked against classical architecture, Reed embraced a Micawberesque optimism, displayed in the opening line of his 1957 Harper’s piece, that the sunset of modernism was just over the horizon: “The architecture we know as ‘Modern’ – the scrubbed and unadorned structures of glass and steel – has, I believe, run its course. Its triumph has never been as complete as its devotees would have us believe. Large sections of the public have never been won over to it, and now its novelty and shock value, despite the arguments of its protagonists about function, utility, and economy, have begun to wear thin.”

Mencken made the same mistake almost three decades earlier in an editorial he wrote for the February 1931 issue of his American Mercury: “The New Architecture seems to be making little progress in the United States. … A new suburb built according to the plans of, say, Le Corbusier, would provoke a great deal more mirth than admiration.”

Carrying forward the architectural revival begun more than anyone else by the Lion of the Classical seems just as difficult today as it must have seemed to most people in 1958, if not more so. And yet “the Modern” persists not because it has gained in popularity – Henry Hope Reed was right about that, and remains so – but because for decades it has applied its massive institutional power to quash popular taste with unapologetic brutality.

In spite of this there has indeed been a strong classical revival. The symposium in Philly on Saturday will explore its prospects.

David Brussat, who spent almost 30 years on the editorial board of the Providence Journal, is an architecture critic in Rhode Island.

Pingback: Henry Hope Reed at 100 | Architecture Here and There