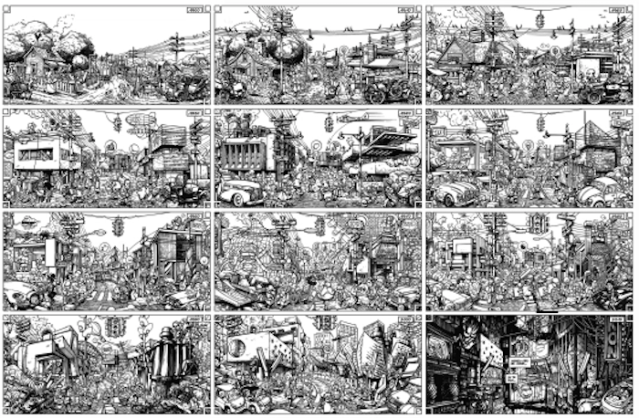

Klaus cartoon, “A Short (Architectural) History of the 20th C., after R. Crumb. (Klaustoon’s Blog)

R. Crumb (Wikipedia)

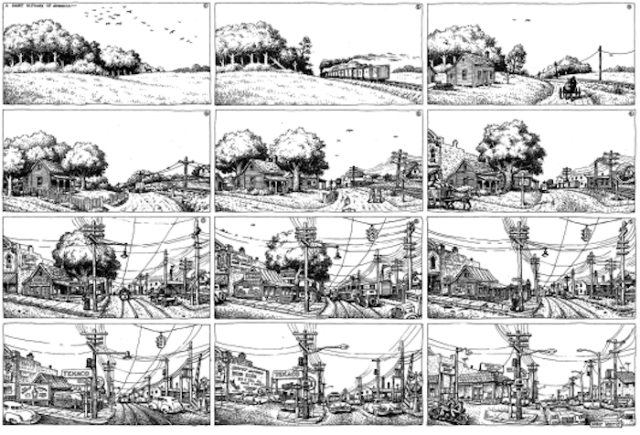

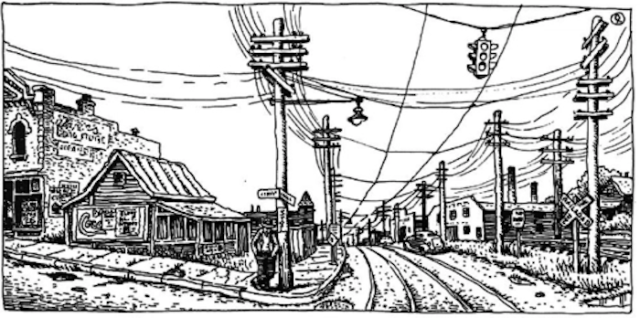

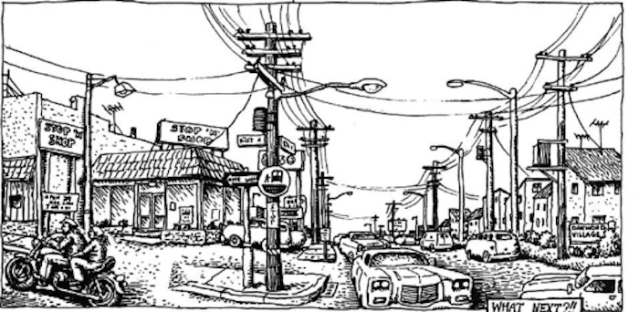

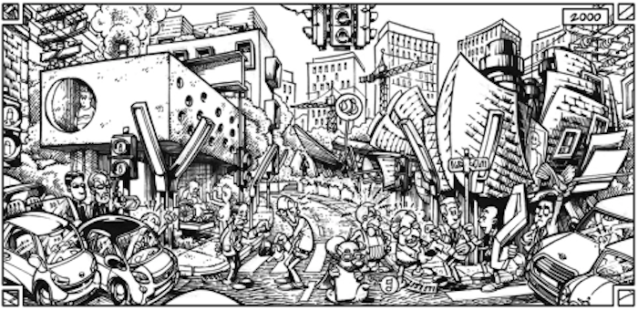

Klaustoon’s Blog has been on my blog roll for years. His intricate sketches satirize the inside baseball among the modern architects, such as one he did on the Pritzker Prize of 2015, which I discussed in “Klaustoon pricks Pritzkers.” I may be wrong, but the enduring fight between modernism and classicism does not register in his drawing. Recently, however, Klaus drew a cartoon in homage to R. (Robert) Crumb, the famous underground cartoonist (“Fritz the Cat,” “Mr. Natural,” “Keep on Truckin’ “) and his celebrated cartoon strip, “A Short History of America,” which satirizes itself. Crumb’s panels depict, over a century, the transformation of a rural landscape into a suburban intersection. Klaus’s own cartoon, “A Short (Architectural) History of the 20th Century,” in tribute to (and including a copy of) Crumb’s, and drawn in a similar mode, focuses on urban architecture, depicting the transformation of traditional urbanism into modernist buildings.

I have been unable to find out the full name of Klaus, though he has been described as “a frustrated cartoonist that lives in an old castle in Europe.” And I have little to say about either Crumb’s or Klaus’s histories, except to note that Crumb did not like modern architecture. Here is a quotation of Crumb taken from Peter Poplaski’s 2005 Crumb Handbook:

As a kid growing up in the 1950s I became acutely aware of the changes taking place in American culture and I must say I didn’t much like it. I witnessed the debasement of architecture, and I didn’t much like it.

Here, from Terry Zwigoff’s 1995 bio, is another quote that feels right:

I think Crumb is, basically he’s the Bruegel of the last half of the twentieth century. I mean, there wasn’t a Bruegel of the first half but there is one of the last half, and that is Robert Crumb.” (Robert Hughes in Crumb (Terry Zwigoff, 1995).

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569) was among the first Dutch painters to work after religion was no longer the conventional subject of art. Bruegel specialized in rural landscapes not quite as hellish as those of Hieronymus Bosch, but hardly idyllic. In their histories of America, Crumb leans more toward Bruegel while Klaus leans more toward Bosch.

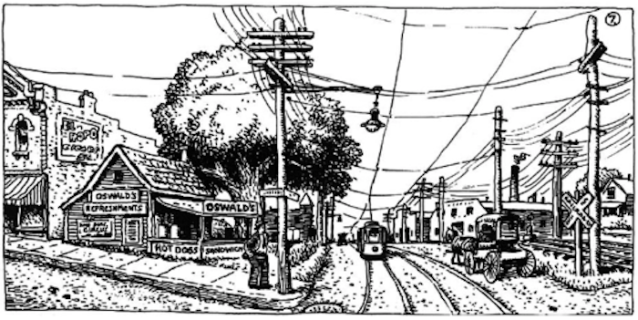

Both drawn histories are rich in detail, and it is fun to examine each frame closely. If you are of a certain age, both artists evoke delightful memories of unnoticed aspects of, in the case of Crumb’s, the suburban environment and, in the case of Klaus, an urban environment, with its succession of modernist buildings, most of which are lampoons of the work of identifiable modernist architects. Both Crumb and Klaus frame their histories as decade-by-decade battles between owners of land on either side of the road.

Both are cartoons by cartoonists, but both are also inspired historians and urbanologists. Both, it seems, did meticulous on-site research. Klaus could not, of course, avoid seeing it any more than the rest of us can. Crumb, in describing his research style to a reporter from TIME magazine, observes a phenomenon I’ve often described in my blog regarding a common defense mechanism – the ability to faze out so many of the ugly aspects of our built environment. Or in Crumb’s words, what we are “trained to ignore”:

Decades later, TIME magazine revealed that, in the late 1980s, Crumb persuaded a photographer friend to drive him through commercial streets and “bleak, just-built suburbs” of California and photograph “ordinary street corners” … “methodically us[ing] the camera to capture what our increasingly inattentive eyes have been trained to ignore.” For Crumb, “[this] material has not been created to be visually pleasing, and you are not able to remember exactly what it looks like. But this is the world we live in.”

Not long after I saw Klaus’s own history (all of the frames of which are pictured separately in A Short (Architectural) History of the 20th Century in a larger size) in tribute to that of Crumb, he published a post analyzing Crumb’s “A Short History of America.” Each of its 12 frames are pictured separately in a size that may be easily examined, or resized even larger for even closer inspection.

By the way, in his two posts on Crumb’s history, Klaus repeatedly denigrates his own artistic talent next to that of Crumb. Please, I would beg to disagree. Klaus merely labors under the difficulty that the scenes he draws show more modern architecture, but their ugliness should not be attributed to his pen.

R. Crumb’s “History of America [1850-1970],” published in 1979. (Klaustoon’s Blog)

It was fun reading your article. Unearthing the mysterious character is surely a great challenge, and you have done justice. I too love his sketches and have been following him to know a great deal about his work. Creativity and engineering go hand in hand for architecture students like me.

LikeLike

Thanks very much, Donnie. He has such an erudite hand. I’d love it if he took up the style wars battle between modernism and classicism. Whatever side he may be on, his take would be a laugh riot!

LikeLike

Thanks for the reminder of the Crumb cartoon, David. The late Hank Dittmar had a print of it on the wall in his office, and we often marvelled over its veracity and acuteness.

LikeLike

Your welcome, Anon. I knew Hank, not well, but well enough to easily imagine his having hung the R. Crumb masterpiece on his wall. I do not know him well enough to imagine him wanting to inhabit the first frame unto eternity, but enough to trust he would not want to occupy the last frame for long. RIP, Hank.

LikeLike

Pingback: An Analysis of “A Short History of America” by Robert Crumb. – LeveVeg

While there are no cities without planners, Alain Bertaud’s book “Cities without planners” points out that the world-wide range of cities goes from Houston, where there is almost no government intrusion into land markets, to some capital cities such as Brasilia, which were almost completely centrally planned. The experiences within this range has persuaded Bertaud that cities that rely more on markets and less on planning to determine land uses are more affordable, more mobile, and more productive. Urban planners are micromanagers.

With cities across America being the battle grounds of crazed outrage…

What futurists get wrong

– Technical change vs. technical adoption

– The fashion of what goes into societal re-design

– People don’t like to be told what to do

– We can only validate patterns that are moving forward. What the Covid-19 virus exacerbated was something we already knew about cities…….they were failing and depopulating.

Jane Jacobs, wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she argued heavily that urban planners didn’t understand how cities worked. If that’s all she had said, it would have been fine and I’d have agreed with her. Then she went on to claim that SHE DID understand how cities worked. She considered Greenwich Village, the remnant of nineteenth-century housing developments that were considered abominable in 1890, to be the epitome of urban life. At the time, urban planners hated the book, but one generation later, planners took it as gospel, even though her understanding of how cities worked was as and inept as that of the planners she criticized. Jacobs’ fondness for lowrises ignored the fact that, between about 1900 and 1990, almost no new buildings like that were constructed anywhere in the US. The reason for this was economics: Americans were no longer willing to climb four flights of stairs to get to their homes or offices, but the cost of adding an elevator was so great that it only penciled out in buildings that were six or more stories tall. The American’s with Disabilities act made elevator adoption paramount on buildings that weren’t economical to install or build. Jacobs, and the urban planners who later followed her, had fallen in love with a building form that was unmarketable without subsidies.

LikeLike