The Frick Collection, 70th Street facade. (ny-architecture.com)

Boards of institutions always seem to want to do more for the institution than the institution needs. And whenever a board proposes to do something, it is normally more than is judicious, often a lot more – a unwitting attack on the values of the institution itself.

Exhibit One: The proposal to stuff more stuff into the Frick Collection, the house museum cum art gallery on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. The board of the Frick has proposed more than a few abortive renovations of late and finally decided to push one of relative modesty by modernist Annabelle Selldorf. Even I supported the Selldorf plan when it was unveiled, because Selldorf’s exterior revisions seemed to be at least minimally classical, not modernist as is invariably the expectation. It is important to show the public that new classical work of a high order can be done, and that beauty is not something lost to the past.

Such demonstrations are rare. My favorite is the 1990 classical addition to the 1904 John Carter Brown Library, on the Brown University campus in Providence. God, what a row that must have caused when first proposed! Its board deserves congratulations, as does the huge firm of Hartman-Cox, from Washington, D.C., which designed an addition slightly less rococo than the original, something virtually unheard of then. Beautiful!

Similar exterior changes were offered by Selldorf for the Frick, and approved last year by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. Unfortunately, in attempting to shoehorn new space into the building, Selldorf proposes to demolish the circular Music Room, designed by John Russell Pope in the 1930s, and the Reception Hall, designed by John Barrington Bayley in the 1970s. Both were additions to the original 1914 mansion of steel magnate Henry Clay Frick on Fifth Avenue, designed by Thomas Hastings, but were so well conceived that the luxuriant domesticity of the house was enhanced.

Critic Catesby Leigh, writing in City Journal, the quarterly of the Manhattan Institute, describes in “Degrading a Masterpiece” the complex give and take supposedly needed to accomplish the expansion that the Frick board desires:

The plans have some positive aspects. It will be wonderful for visitors to climb the original mansion’s grand staircase to the second floor, where Pope converted family quarters into museum offices. These will now be used for the exhibition of small paintings, drawings, and works of decorative art. And the Frick has long emphasized its need for a larger auditorium, better conservation facilities, and better accommodations for school groups. But to degrade the existing house museum would be a terrible mistake.

Here Leigh, with his inimitable facility for painting architecture in words, describes why the Music Room must be saved:

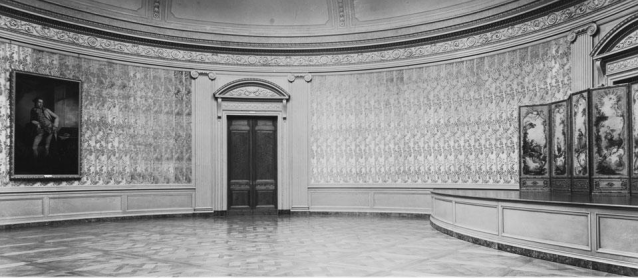

Pope’s Music Room—mainly used for film screenings and lectures but best known as a much-loved chamber music venue—opens off one side of the Garden Court by way of two handsome little lunette-shaped, wood-paneled vestibules that reconcile the court’s rectangular plan with the Music Room’s circular form. Such refined architectural sequences are one of the Frick’s glories. Above the wainscot, the wall of the Music Room is covered in golden damask enriched with a leafy sylvan pattern. A floral rinceau runs along the frieze above. Elegant doorways are framed by Ionic pilasters. The flat ceiling extends from a cove, with ornamented ribs extending from the circular skylight’s elaborately molded frame. This room would make an excellent special exhibition gallery, and in fact it was designed to serve as a gallery. It is an essential part of one of the most superbly orchestrated spatial ensembles America has to offer. Along with the rest of this ensemble, it should be left intact.

Leigh adds:

[Selldorf] and the Frick want to atone for the destruction of the Music Room and its vestibules by retaining the room’s original doorways. But great architecture, in a room as in a building, is like a great painting or sculptural work, in which every form reinforces every other form in constituting a whole that is not only greater than the sum of its parts, but that casts a spell—precisely because of its formal consistency. Where’s the magic in retaining beautiful doorways that simply point to the poverty of their new architectural setting? …

In informing the New York Times that she wanted her Frick renovation to “have its own identity,” Selldorf gave the Pope-Bayley precedent the boot and demonstrated that she is the wrong architect for the job.

Soon the board will take its plans to the city’s Board of Standards and Appeals, the last chance to pause before committing an unforgivable desecration. Let’s hope that board will read Catesby Leigh’s insightful assessment, which all viewers of this post should read in its entirety.

The Frick constitutes a single artistic entity that flows through Hastings, Pope and Bayley over six decades without a burp of aesthetic inconsistency. These sorts of architectural masterpieces are increasingly rare in New York, indeed in America. If the Frick’s board wants to stuff more stuff into the Frick, let it buy another building nearby and park its ambitions there.

The Music Room in 1935. (frick.org)

Rendering of proposed Frick renovation, 70th Street facade. (Selldorf)

The Frick is falling to the same Edifice complex which has destroyed many institutions (See: the Cooper Union). It is my favorite museum in NYC.

LikeLike

I agree. John and I were at the Frick last spring for the Moroni exhibit, as well as a lecture on Tintoretto in the lovely auditorium. best, Philip

LikeLike