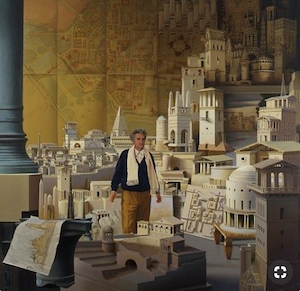

“A Classical Perspective” (2012), by Carl Laubin. (carllaubin.com)

The British-American painter Carl Laubin specializes in classical buildings assembled en masse on canvas. I first came face to face with one of his works at the celebration, in 2013, of the Richard H. Driehaus Prize for architect Thomas Beeby and the Henry Hope Reed Award for historian David Watkin, in Chicago. How pleased I was to learn that this year’s Reed laureate was Laubin himself. The good news called to mind his masterpiece, “A Classical Perspective” (2012), with which I had flirted, nay, romanced six years ago.

It was commissioned by Driehaus to honor his prize’s first ten recipients. It is a large painting of buildings designed by each laureate and nestled on hills surrounding a river that flows through an indescribably pacific imaginary scene. I was transfixed, and over two days happily followed the capriccio – as such a painting (capricci in the plural) is known – to several venues as it wandered around Chicago, serving as centerpiece for each event associated with the festivities, hosted by Driehaus, the Chicago philanthropist, and the University of Notre Dame, which sponsors the awards each year.

Wrigley Building (left), Tribune Tower.

Chicago, where I was born, is not considered a mecca of architecture for no reason. Even its modernist buildings, mostly skyscrapers, look good there because they are chiefly seen in the elegant jumble of their collectivity – winding along Lake Michigan and the Chicago River – rather than in the pitiless glare of their mostly sterile individuality. By far the city’s most impressive if not applauded buildings, however, are its classical buildings, especially its most celebrated skyscrapers, the Tribune Tower (1925) and the Wrigley Building (1920) as seen together from across the river on the second city’s Magnificent Mile (Michigan Avenue). It may be the ensemble that in true spirit most resembles the grandeur of classical Rome. In fact, although vertical rather than horizontal, it looks like a Laubin come to life.

“Ten Years of the Driehaus Prize,” a page on Laubin’s website, describes the creation, in the course of a year, of “A Classical Perspective,” using prose and images of the painting at various stages. Concluding with the image at the top of this post, Laubin has put together different versions in color of the full painting, finely wrought sketches of the picture as it evolved, line-drawings of close-up details of the finished work, and colored segments set into line drawings, interjecting between them explanations of the progression in his mind of how the work moved inexorably toward, I’d say, perfection.

I quote several excerpts, but strongly urge readers to click to the link and read the entire essay. Of the general idea of the landscape, Laubin writes:

The composition is loosely based on the formula for a classical landscape painting as described to me by John Outram in 1987 when I was doing a painting for him, “Imago Terrarum.” Basically, in his formula, one enters the picture from the countryside, across a bridge, over a stream which winds its way into the painting. One passes through the agrarian countryside to the town with its harbour and upwards through different levels of civilization before arriving at the Acropolis where the ideas reside.

He describes his progress through the stages of painting:

The composition continued to develop and change on canvas over the next seven months; buildings coming and going and shifting minute distances. I also found the landscape changing in the painting as the seasons progressed in reality, reflecting what I would see on my walks in the countryside. I became determined to finish the painting before autumn which would require a major shift in the tonality of the work.

Here is how he stitched together diverse work by the ten laureates:

In the completed work, I think the diverse approaches to classical or traditional architecture do combine to create a harmonious composition through their shared principles with surprising resonances occurring in unexpected juxtapositions. I thought this was true of the Atlantis/Pitiousa/street of Robert Stern Villas sequence mentioned earlier. I found the middle ground peninsula with a slightly Mediterranean flavour is another. Tropical residential buildings by Duany Plater-Zyberk and Jaquelin Robertson establish a Mediterranean influence that is continued in buildings by Léon Krier, Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil, Michael Graves and Robert Stern. Here buildings from Florida, Jeddah, Egypt, Greece, the Dominican Republic and New Jersey sit comfortably side by side. I can also see ripples of influence that run through the centre of the main town. The Moorish influence that can be found in many of Manzano Martos’ restoration projects find sympathetic neighbors in El-Wakil’s Jeddah Lighthouse and mosques, and Duany Plater-Zyberk’s Alys Beach House at one end of Manzano Martos’ Calle San Fernando and Allan Greenberg’s Rice University Humanities building at the other end. Even Porphyrios’ Duncan Galleries in Nebraska does not seem out of place next to El-Wakil’s Corniche Mosque both constructed of lively, highly articulated forms that catch the light dramatically.

Leon Krier and his work. (Pinterest)

Laubin’s works mainly depict the most notable architecture of a single bygone master, or, as here, a collection of buildings by various notable architects. As Laubin notes above, “[c]lassical or traditional architecture … combine to create a harmonious composition through their shared principles with surprising resonances occurring in unexpected juxtapositions.” Laubin’s genius is not to create that harmony by himself alone but to assemble the buildings to reflect that harmony as time and nature would do themselves, applying patience and the guidance, so to speak, of architects down through the ages. In “A Classical Perspective,” Laubin conveys his most important message, which is that there is no reason the same beauty cannot be achieved by architects today.

As so many indeed have done, which the Driehaus Prize proves, and which the winners of the Henry Hope Reed Award, dedicated to the late New Yorker who founded the classical revival, demonstrate with inimitable scholarship, year after year.

***

[Note: Between Jan. 31 and Feb. 13, the survey results from the poll on classical versus modernist architecture have swung from No (the modernists) leading 92-8 percent to Yes (the classicists) leading 64-36 percent. Please vote. The deadline Feb. 26.]

Detail of “A Classical Perspective” showing Quinlan Terry’s Richmond Riverside (1989)

Marvelous piece, David. Thank you

LikeLike

My pleasure, Ed. Not difficult to praise beauty!

LikeLike

Beautiful images – nothing in the cities sticks out like a sore thumb – so pleasing to the eye…

LikeLike

The amazing thing, Nancy, is how easy it all is. Not that designing or building a beautiful house is easy, but the models are all around us, the techniques are available and up to date. Prejudice in the design community is the only obstacle. Since the design community seems to want ONLY sore thumbs to stick out on city streets.

LikeLike

Another distinction of the buildings Laubin paints is that they CAN be assembled into an image of a city, because they were mostly conceived as parts of a city, either in fact or potentially. Imagine the difficulty of making such a painting with works by the Pritzker Prize and one appreciates the importance of this aspect of classical design.

LikeLike

Rem Koolhaas has already done it for us – his collage of photos of iconic modernist towers assembled in a desert makes the point precisely. But of course he does not follow his own apparent advice. Odd duck. What is it with him?

LikeLike