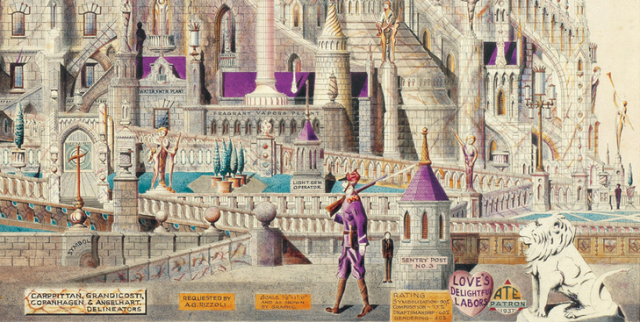

Detail from “Mother Symbolically Recaptured” (1937, by Achilles G. Rizzoli. (pomegranite.com)

I tried in my last blog, “The architecture of the wife,” earlier today, to link to a column I wrote in 2004 to honor my late mother, Mona Brussat, and downloaded from the archive of the Providence Journal. It didn’t work, but I did get the text and so here is that plus the illustrations that went with it. The column was originally entitled “Sketching the mother of all moms.”

***

THE BUILDING ABOVE, festooned with statues of mothers by the score, is the work of A.G. Rizzoli, a draftsman who worked for an architecture firm in San Francisco. His most extraordinary drawings, from the late 1930s, were done not for his boss but for his mom. This one, drawn in 1937, is called “Mother Symbolically Recaptured.”

Last week, the American Society of Architectural Illustrators held its annual meeting in Providence. I had hoped to attend. A column chronicling the convention would have offered an opportunity to discuss Rizzoli, but it just did not occur to me. Rather, I had planned to focus on the poster art for the event, featuring a sketch of the Providence County Superior Court, drawn in 1927 by Chester B. Price for the firm of Jackson, Robertson and Adams.

H.P. Lovecraft, the late Providence writer of mystery tales, praised the courthouse design in a March 20, 1929, letter to The Sunday Journal. But it included an annex (visible in the poster) across South Main Street that would have required demolishing a string of old warehouses called the Brick Row, on the Providence River. Lovecraft attacked that part of the plan. “Behind it,” he wrote, “lies the far broader clash of city-planning ideals which it typifies; the eternal warfare, based on temperament and degree of sensitiveness to deep local currents of feeling, between those who cherish a landscape truly expressive of a town’s individuality, and those who demand the uniformly modern, commercially efficient and showily sumptuous at any cost.”

(Brick Row was torn down in 1929, but the annex was not built. The site is now Memorial Park.)

The idea of writing about Lovecraft’s letter, the poster of the courthouse, and the art of drawing buildings teased me terribly the week before the meeting of illustrators. But I missed the convention because my dear sweet mother died.

Mona is with Bill now. My father died in 1978 after a career that began as a city planner in Chicago, where I was born, and continued in Philadelpha and Washington. I was in no position to memorialize him in newsprint when he died, but in 1995, after the death of his friend Hugh Mields, also a planner, I wrote about them both (“Together again,” July 20, 1995). Did their careers as planners influence my career? Not that I could tell.

My mother’s career as a teacher and actor – the former after her career as a mother of three boys, the latter after she had lost my dad — is, if anything, even more elusive in its influence on mine. We lived in a modernist house once. Later, our more traditional house in Washington was decorated in a contemporary style lifted largely from a furniture store called Scan. Full disclosure: My environment at home was comfortable, stylish and decidedly attractive. But its impact on my later architectural tastes was indeterminate at best.

Photo by William K. Brussat, circa 1957.

My mother did instill in me a love for beauty. Just look at the picture of her helping me read.

Mom was a fantastic educator. Once, I was in her arms, exercising my vocabulary with a slang term for breasts. “No, David,” she said, “They are bosoms.” (This was the 1950s.) My foundation in the terminology of ornamentation was laid at an early age.

Last week, my brothers and I sat on the couch in my mother’s living room going through a batch of pictures Mom had extracted and put aside toward the beginning of her illness. They were pictures of her as a young woman. I was reminded of A.G. Rizzoli and his lovely buildings dedicated to his mom.

After a reclusive life, Rizzoli died in 1981. In 1990, hundreds of his drawings were discovered in his family’s garage. Many of the fantastical buildings were symbolic representations of people he knew — “transfigurations,” as he called them. Those published in A.G. Rizzoli: Architect of Magnificent Visions (Abrams, 1997) reveal a meticulous style that I’m pleased to see has not been totally abandoned by architectural illustrators.

On Tuesday, at the Sol Koffler Gallery, in the Rhode Island School of Design’s recently renovated building on Weybosset Street, I examined the winners of an illustration competition sponsored by the illustrators’ society. The exhibit reveals the impressive artistry gathered in Providence last week. The architectural illustrators are not to blame for the fact that so many buildings designed today are not worthy of their talent.

Rizzoli was devoted to his mother and to an idea that most architects rejected decades ago — that buildings do represent people. No, most buildings do not have bosoms, but the principles of classical architecture are rooted in the dimensions of the human body. Ornament is not merely the jewelry of architecture but its very essence, the expression of a building’s purpose, its aspirations and its place on the street but also in the heart and soul of society.

My mother, symbolically represented as a building, is a temple to love, beauty and truth.

Copyright © 2004. LMG Rhode Island Holdings, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

I loved your mom. She was my fifth grade teacher at Hearst (1968-69). I loved reading with her; she did a lot of theater with us too. I thought of her today, 52 years later, and was happy to find your blog. Mrs. Brussat lives on

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading this piece so much! Very heartwarming. The soulful ending is just beautiful!

LikeLike

Pingback: The architecture of the wife | Architecture Here and There