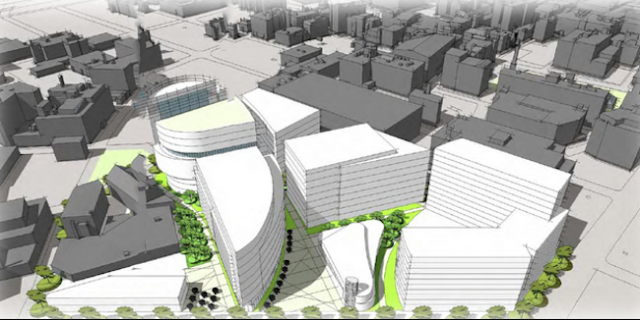

Proposed research campus in I-195 innovation corridor. (Greater City Providence)

All change is bad. Take gentrification. Gentrification is when rich people suddenly take a liking to a poor part of town, move in, raise property values, and force longtime residents – that is, the poor – to move out.

Right? No, that’s not what gentrification is. It is the pejorative term for change. All cities change, and change sometimes creates problems such as making it harder for poor people to afford to live in their neighborhoods. But cities and their neighborhoods always evolve, always have and always will. How to soften its impact on the most vulnerable is the big question.

Michael Mehaffy takes up the topic of gentrification in “Beware of Voodoo Urbanism” on the blog Livable Portland. His urbanist think tank, the Sustasis Foundation, is headquartered in Portland.

Part of his post focuses on the tendency of some people, such as urbanist Edward Glaeser, to chide Jane Jacobs for the fact that after she helped rescue Greenwich Village in the 1960s, property values rose, causing demographic shifts that promoted greater blandness. Glaeser and others claim that this history challenges the wisdom of Jacobs’s thinking about cities, such as her emphasis on the vital importance of old buildings. Old buildings provide affordable space for entrepreneurs who can’t afford to build or lease big new glass boxes for their start-ups. Mehaffy writes:

But Glaeser and other critics seem to miss Jacobs’s point. For Jacobs, the answer to gentrification and affordability is not an over-concentration of new (often even more expensive) houses in the core. Rather, we need to diversify geographically as well as in other ways. If Greenwich Village is over-gentrifying, it’s probably time to re-focus on Brooklyn, and provide more jobs and opportunities for its more depressed neighborhoods. If those start to over-heat, it’s time to focus on the Bronx, or Queens. Or Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, New Orleans.

Providence has been trying to channel the energy of redevelopment quite well over the past several decades, promoting revitalization not just downtown but in neighborhoods such as West Broadway, South Providence and the Jewelry District. But Mehaffy also urges cities that create large new development districts to divide them up into smaller development parcels. Providence has done quite poorly at this, and the results are clear in Capital Center and the nascent I-195 corridor, the latter with its innovation district of proposed large glassy unalluring research boxes.

My upcoming book Lost Providence, due out Aug. 28, offers a sense of the kind of churning that affects evolving cities, whether in neighborhoods or downtowns. I quoted an old column of mine from the Providence Journal, “In defense of gentrification,” written in 2003 about decisions the city made on the way to its current promising revitalization:

One can no more expect landlords to neglect buildings in perpetuity as welfare programs for struggling artists or buck-a-beer joints than one can expect those same tenants to embrace building improvements that will raise their rents. They whistle past the graveyard as the gathering clouds of renaissance darken, praying that their landlord fixes up all his other buildings before getting around to theirs.

There is a certain vitality to dark streets empty most nights until drunks stumble in a rowdy mass from clubs at 1 a.m. But it will be a sad day if City Hall ever determines that the preservation of this vitality should be the urban policy of Providence.

Fortunately for Providence, that policy did not prevail. Gentrification is a word that dangerously oversimplifies that realities of change in cities. Mehaffy’s post is an excellent antidote to that.

Pingback: Antidote to gentrification | Architecture Here and There

David, I have a contrarian theory that Gentrification and Mass Tourism are predictable effects of Modernist Architecture. Gentrification doesn’t happen because historic preservation regulations limit the supply of new housing. Rather it happens because modernist architecture and urbanism limits the supply of the kinds of environments people actually want. Glaeser and others are unable to see that the problem is not that there is so little of what people value most highly,resulting in high prices for that short supply, but that no one is adding to the supply by making new environments that satisfy the same desiderata. If people everywhere could live in beautiful walkable neighborhoods, they wouldn’t have to displace poor people to find them, or spend millions of dollars going to Europe to find them.

LikeLike

21st C. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PATTERNS (toward bottom): http://7g.nz/

LikeLike

Your analysis is perfectly brilliant, Steve. I will put it in a new post soon..

LikeLike

Brussat’s update: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2017/06/17/semes-on-gentrification/

LikeLike

Here are Steigans points for the urbanism of our future:

– The walkable city. Before cheap oil cities were built for slow and local transport. Commuting over long distances was not an option. We will soon be back there again. Cities must be built or restructured so that people can reach most of their daily activities, including work and play using their own muscles, that is by walking or biking. That means that work places and services must be within a short walk from home.

– City cells. To be walkable, all basic needs must be within walking distance. That means that the city must become a multi-node, multi-cellular city. A city of towns. Some needs that are not daily necessities could be found farther away, like an over-laying grid.

– Quality of life. The city nodes must have a sufficiently rich cultural life to satisfy a wide range og needs. Cultural consumption is normally less energy an material demanding and also gives life and attrativeness to the city environment. Here I think not only of culture for the people, but also of culture by the people. The city must give ample room for the creative activities of the citizens.

– Self sufficiency. The city must become self sufficient and self sustaining to a very large degree. Buildings must produce as much energy as they consume. A certain amount of food production must take place in the city. Sewage must be treated so that phosphates and nitrogen is contained and circulated back to farming.

– Durability. The modern tendency of use-and-throw is creating waste mountains that threaten to strangle the big cities. Durability and reusability are the new modern. Energy, water and other material resources are stretched thin today. There is small room for growth. So economic use of resources will be crucial.

– Urban qualities in the countryside. To contain a too great influx of new millions into the megacities, it is crucial to give the countryside some urban qualities. Those qualities that go for the city cells should also be developed in smaller rural centres, when it comes to jobs, housing, culture, recreation etc.

A little different than what Stalin proposed 🙂

– The sustainable city of the twenty-first century: https://steigan.no/2011/10/04/the-sustainable-city-of-the-twentyfirst-century/

LikeLike

Grünerløkka in Oslo is nicely gentrified, it was built very fast and poorly for the working class, but still has some timeless patterns attracting rich people. It was saved thanks to urbanist Audun Engh, communist Pål Steigan and other. They both left the struggle with a deep hatred against modernism and their architects, who wanted to tear the whole area down. Steigan eventually decided to flee it all, settling in a small Italian town, Tolfa, where he found the urban qualities he desires. Steigan’s son is now a profiled anti-modernist, fighting to preserve traditional architecture.

Steigan has now left state-socialism, condemning it as a failed experiment, and is in his new version of communism approaching the commons as a new model. That’s too a reason for why he settled in Tolfa: https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/tolfa-in-italy-a-future-hub-for-the-commons-in-europe/2014/06/25

– Tolfa, il convento e Allumiere su Rai 2: http://steigan.no/2016/11/28/tolfa-il-convento-e-allumiere-su-rai-2/

Steigan’s newly bought monastery looks like the perfect location for future commons conferences. He did of course buy it together with some of his rich friends supporting his work. I think he would be happy to arrange conferences for traditional urbanism, new urbanism and so on here. Just a tip for an excellent localization for future relevant conferences in Europe.

LikeLike

Ps! It was the buying of the monastery by Steigan and his rich friend that attracted RAI-TV to make this very nice documentary from Tolfa 😉

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Leveveg, for your extensive comments on urbanism, in too much depth for me to muster a reply for now. Again, many thanks.

LikeLike