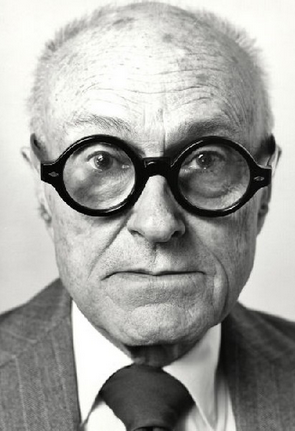

Photograph of Philip Johnson backdropped by photo of Nazi rally. (Vanity Fair)

Mother’s milk flowing from her gentle soul, a good friend expressed at lunch yesterday her dismay at the fascist tendencies of modernist architect Philip Johnson. She is no fan of his buildings (there are two in Providence), but she was unaware of his Nazi past. This was hardly surprising, given her intensely local focus on architecture.

Coincidentally, another friend of mine, who has tutored me on many aspects of the connection between modern architecture and fascist ideology, sent me “You can easily be a bad person and a great architect” from Dezeen. Its key error is to equate Johnson’s work with great architecture.

Here’s a piece in this month’s Vanity Fair, “Famed Architect Philip Johnson’s Hidden Nazi Past,” by Marc Wortman, excerpted from his new book 1941: Fighting the Shadow War.

See also this piece, “When a Famous Architect Is Also an Anti-Semite,” by Rachel Shukert in The Tablet two years ago. “I love Philip Johnson’s buildings not in spite of him,” she writes, “but to spite him.” Huh? This is a very long and erudite essay that focuses on the slave-owning Jews of early Suriname. Whether she rectifies the distinction she makes via the word spite, and how much it bears on the question of fascism and modernism, I leave to others.

The Dezeen article is actually a much briefer collection of quotes from people who know about Johnson’s flaws but love his buildings anyway.

Nazi past: American journalist Marc Wortman has chronicled Johnson’s role in promoting the Nazi agenda in the US in his new book. But many readers were underwhelmed by the revelations.

“Maybe I have no soul, but to me this doesn’t mean anything,” wrote Jan Limon. “Millions supported the Nazis at the time and they were both ignorant and in denial about exactly what evil was taking place.”

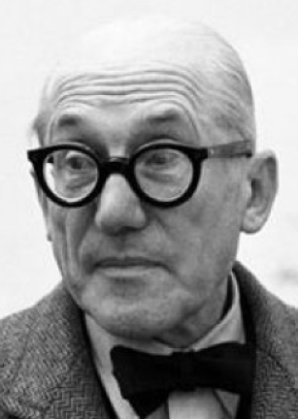

“We have to remember figures like Mies [van der Rohe] and Le Corbusier were also at least ambivalent towards Fascism,” added Davide. “Fascism and Modernism – especially early Modernism – did have some common ground in their striv[ing] for permanent, radical, functional methods that essentially disregarded human conditions.”

In 1939, seven years after curating the MoMA exhibit that introduced modern architecture to America, Johnson rode into Poland as a guest of the troops of the invading Wehrmacht. He later returned to the United States, where he founded an organization, the Grey Shirts, to support the fascist ideology here. He was an avowed anti-Semite. Later in his career he laughed off his years as a Nazi sympathizer as a youthful peccadillo, and it became a sort of faux pas among modernists to refer to his fascist tendencies – which, to be sure, were not altogether rare in the United States. He seems to have forsworn Hitler but did he ever forswear his anti-Semitism?

Wortman, in Vanity Fair, uses this passage to bring his long article to its conclusion:

Years later, in 1978, the journalist and critic Robert Hughes interviewed Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, who had spent 20 years in prison for his crimes. Hughes described the meeting in an article in The Guardian in 2003—he had just come across a lost tape recording of the conversation. He wrote:

“Suppose a new Führer were to appear tomorrow. Perhaps he would need a state architect? You, Herr Speer, are too old for the job. Whom would you pick? ‘Well,’ Speer said with a half-smile, ‘I hope Philip Johnson will not mind if I mention his name. Johnson understands what the small man thinks of as grandeur. The fine materials, the size of the space.'”

Johnson

Le Corbusider

None of it seems to matter to his acolytes today, any more than Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s desire to become Hitler’s Speer, or Mies’s effort to persuade the Nazis, in the mid-30s, with Goebbels’ help, to accept modernism as the design brand of the Third Reich. Or Le Corbusier’s work for the Nazi puppet Vichy government of France during World War II.

I told my friend over lunch how I feared, with regret, that the modernist architects who fled Hitler’s Germany in the ’30s may nevertheless have brought a certain iron fistedness with them – perhaps, among some, in part because of their flirtations with communism during the Weimar and early Nazi years. Might there be an instinctive totalitarian tendency that subsists as part of the DNA of a German character that arose from centuries of rule by feudal lords commanding the countryside from castles long before Germany was united under Bismarck? (I’m a quarter German.) Is there something in the German mindset that permitted a highly intellectualized society to follow the beast Hitler step by step on a course toward brutalism and war?

Is there any of that mindset in the modernist establishment today, given its suppression of diverse tendencies in architecture?

I am only asking questions, not positing answers. Still, most notables and celebrities at the top of their fields in America, and even more so in Europe, would be hounded out of respectability for expressions of belief that characterized modernism’s founding theorists. What this has to say about architecture’s role in a deeply dangerous, divided, unhappy world is a topic worthy of discussion.

Some classicists and traditionalists are just as afraid as modernists are of having this discussion because of the connection between the architecture they like and the bastards that history has placed within its walls. The big difference is that traditional architecture was the default architecture for 3,000 years. A tyrant could no more choose between a traditional palace and another sort of palace than a Hittite could choose between a chariot and a Maserati. Modern architecture, on the other hand, sprang from a more recent past amid a world that contemplated embracing ideologies – fascism, communism, etc. – that we now mainly associate with dystopian films. A choice was possible and the wrong choice was made.

The importance of that distinction manifests itself clearly in the very look of the buildings that arose from either span. Should humankind follow the sensibility of the span that encompassed millennia or the span of our darkest recent decades. Good question.

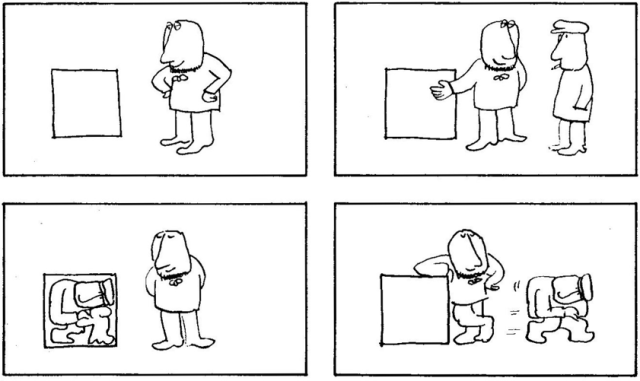

Sketch by Louis Hellman

Umm…http://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2014/09/21/1411327469226_wps_1_B4ACM3_National_Socialism.jpg

LikeLike

Fascism and classicism is an old story, albeit essentially false in that fascists merely used Western civ’s default design template. Fascism and modernism is a new story (or an old one that’s been suppressed). What most would say of the totalist state today – sterile, foreboding, ominous, insensitive, inhumane, bureaucratic – adds up to modernism.

LikeLike

Perhaps my bravura post on the Donald’s penis-envy architecture should run about now.

LikeLike

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that The Donald sheathed the traditional Hotel Commodore in reflective glass, thereby destroying any sense of scale and proportion. https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/f0/50/1d/f0501d83d023d1bdfe47349f47d40b21.jpg

LikeLike