My friend Nathaniel Walker, who got his doctorate at Brown last spring and now teaches architectural history at the College of Charleston, has contributed this essay.

* * *

From the Ground Up: How Architects Can Learn from the Organic and Local Food Movements

By Nathaniel Robert Walker

As a supporter of traditional urban design and a believer in the contemporary relevance of traditional architecture, I cannot count the number of times I have heard generally well-meaning, otherwise reasonable people say the words: “Well, we cannot pretend that we are building in the nineteenth century.” This statement envelops within its svelte hide a veritable swarm of debatable assumptions, many of which lie at the heart of global architecture culture’s current malaise.

I find it is usually useless to attack these assumptions directly by asking complicated questions such as “What is it about symmetry or ornament that makes them the exclusive property of any particular historical period, considering the fact that they are found almost everywhere, in almost every era?” Instead I have lately taken to nursing the argument from another, indirect angle — an approach that has, to my surprise and delight, enjoyed some success in pubs and classrooms around the world. I ask the Modernist: “May we pretend that we are eating in the nineteenth century?” The initial response is a quizzical stare. I follow up: “What I mean to say is, is it progressive or backwards to eat locally sourced, organically grown food? What about heirloom tomatoes? And how about cuisine inspired by traditional recipes drawn from local cultures? Is any of this acceptable for modern people? Is that a lemongrass curry on your plate, by the way? Rather old-fashioned, that.”

It is fun to take this line of questioning further. What would our dinner tables look like if culinary culture were half as hung up on the rigid rulebook of progressive aesthetics as architecture culture is? Would we be allowed to eat bread or rice, or would they be forbidden due to their unspeakable antiquity? Would regional fare using locally harvested ingredients be celebrated as part of a rich, diverse, interconnected world of unique traditions, or would it be condemned as provincial nostalgia?

It is fun to take this line of questioning further. What would our dinner tables look like if culinary culture were half as hung up on the rigid rulebook of progressive aesthetics as architecture culture is? Would we be allowed to eat bread or rice, or would they be forbidden due to their unspeakable antiquity? Would regional fare using locally harvested ingredients be celebrated as part of a rich, diverse, interconnected world of unique traditions, or would it be condemned as provincial nostalgia?

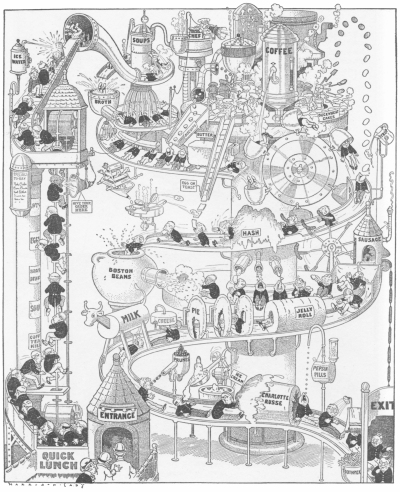

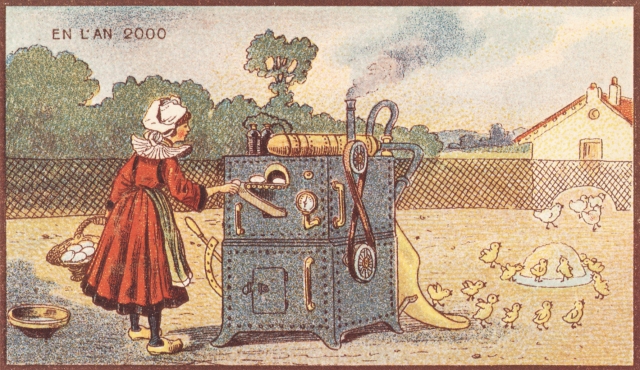

The histories of food and modern architecture have, actually, long been intertwined, on many levels. By the early 20th century, many people in the Western world assumed that no aspect of our lives would go untouched by the rise of industry, including the way we eat. (See adjacent cartoons!) Prominent architects such as Adolf Loos argued that simplicity in architecture should be matched by simplicity in cuisine, because truly modern people had no need for ostentatious ornaments either on their façades or on their dinner plates. By the late 1930s, high-tech, industrialized domestic kitchens had been formulated as a cornerstone of national (and often racial) progress by everybody from Good Housekeeping to the Italian fascists. Famously, many technology gurus predicted that the irrational, animalistic pleasures of eating would be abolished altogether when nutrition came in pill form.

After World War II, Americans in particular were enthusiastic about the cheap and convenient edibles that industry was bringing to the table. TV dinners, synthetic factory foodstuffs like BAC-Os®, SPAM® and Velveeta®, monosodium glutamate and eventually microwave-radiation, push-button cooking were all rolled out as triumphs of the age, tokens of modernity to be embraced alongside automobiles, rockets to the moon and, of course, modern architecture. What backwards fool would attempt to hold their ground against the inexorable forces of evolutionary destiny by slow-roasting a free-range chicken with homegrown herbs — let alone insisting that the bird be gently raised without steroids or antibiotics and humanely slaughtered?

And then the tide turned. Many of today’s young progressives — many of whom were raised in the TV glow of suburbia absorbing luminous, corn syrup-based “fruit snacks” — have whole-heartedly rejected industrially processed, chemical-infused products in favor of foods only their great-grandparents would recognize. And remarkably, such organically produced victuals are not ridiculed as the product of nostalgic reaction, but lauded as the fuel of cutting-edge progress! What would you expect to see, after all, on the plate of a black-frame bespectacled, elegantly disheveled Modernist architect: a goosh of Cheez Whiz®, or a wedge of Adirondack chèvre? More to the point, while most of us would, of course, allow someone to consume Cheez Whiz® if they desired it (especially on a Philly cheesesteak), what tyrant would insist that only Cheez Whiz® be offered to the public due to its privileged status as a lovechild of industrial modernity? And who among us would today abstain from the “unnecessary” ornaments of saffron, cinnamon, nutmeg, black pepper, habanero, etc., in the service of rationalist minimalism?

When our thoughtful Modernist architects shop for food they are generally open-minded about traditional growing and cooking practices — I believe they should be equally open to traditional architectural ingredients such as locally sourced natural materials, organic symmetry, humanistic proportion, craft production and “applied” ornament. As we can see in our farm fields and pastures, old things are not invalid simply due to their age. Indeed, many of the modern promises about the future of food have turned out to be hollow, and one of the chief challenges of our times is figuring out how to undo some of the damage of industrial agricultural practices.

That said, I also believe that our more conservative traditional architects have something to learn from modern food culture: good vegetables may be grown according to ancient methods, but food processors are really, truly useful for turning them into decent soup! Even more importantly, we can and we should revive local agricultural and culinary cultures, but we must also seize the blessings provided by our globalized, Internet-sourced recipe collections, most of which draw from a world’s worth of traditions, and rightly so! Would we willingly go back to the days when Western palates were ignorant of the joys of injera, bibimbap, and ghee? The old must be synthesized with the new, the local with the global, and the traditional with the modern, if a living cuisine or a living architecture is to prosper. We must reject the simplistic monoculture of orthodox Modernism, and we must continue to relearn and revive lost ideas and practices, but we must not fall back on a myopic, limited traditionalism that refuses to look outward and onward in search for good ideas.

If all of our architects were as liberated as our local farmers and chefs, our cities would be designed and built from the ground up, cultivated in the fertile, living soil of our shared cultural resources, past, present and future. The main job of architecture is not to convey history but to make it, ideally by being beautiful, useful, and sustainable — a timeless feast, at the common table.

Nathaniel Robert Walker is an assistant professor of architectural history at the College of Charleston, in Charleston, S.C.

Pingback: Preservation in Charleston | Architecture Here and There

Pingback: Photos of downtown Boston | Architecture Here and There

Hi David, I’m amazed how someone can mix architecture and food in an interesting way. And you just did it with this post. 🙂

LikeLike

I asked Nathan to write the piece for my blog, having heard him make some of these points in conversation. But to be clear, the article’s brilliance is his. I merely published it.

LikeLike

Get it! Thanks for your clarification.

LikeLike

Pingback: Nathaniel Robert Walker: Architecture and food | yummybhavu

So inspiring

LikeLike

This was a wonderful read. I think the comparison is nuanced. I do wish the author had delved deeper into the concept of accepting old as new or progress more easily in some domains than others. He lingered on the example a bit too long for my curiosity

LikeLike

very good

LikeLike

Pingback: What Is Old Fashioned? On Food and Architecture | williamsway1

Read this with great delight!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Travels with Mary and commented:

Great post!

LikeLike

Fabulous post!

LikeLike

Great work. By One Dollar Hosting

LikeLike

Amazing. Simply, amazing.

LikeLike

Very interesting read! Thank you for the thought provoking post.

LikeLike

Pingback: What Is Old Fashioned? On Food and Architecture | adeyemirotimi

Wat betekent het? Ik kan geen Engels

LikeLike

Great blog! Thank you!

LikeLike

Pingback: What Is Old Fashioned? On Food and Architecture | jawad2015blog

Pingback: N. Walker: “Babylon Electrified” | Architecture Here and There

Reblogged this on todaysdiywoman.

LikeLike

Informasi Anda Sangat Menarik Dan Bermanfaat

LikeLike

Thank you

Fantastic Blog

Good luck

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

http://www.filemissile.net

“””

LikeLike

Click this please . Need help http://mutiaraarienygoblog.wordpress.com thank you

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Isla en Código.

LikeLike

Wspaniała grafika !

LikeLike

Reblogged this on shinytinystuff.

LikeLike

Interesting ideas. I agree we need to start to making tomorrow’s spaces small havens and more naturally eloquent.

LikeLike

is he responsible for the pastry pistol a child was reprimanded or arrested for?

LikeLike

waooo

LikeLike

Reblogged this on lindsaynicoleroach.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on rosettass.

LikeLike

very good

LikeLike

Reblogged this on humnamehmood.

LikeLike

Interesting read I had with your post.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on kimmyfinlay.

LikeLike

Ancients were having Strong Architectures and Healthy Foods…..

Environmental Services in California

LikeLike

Reblogged this on On the Seafood Diet.

LikeLike

Eat, Love and Money 😀 visit lovewithpic.wordpress.com

LikeLike